Looking Beyond Penn Station

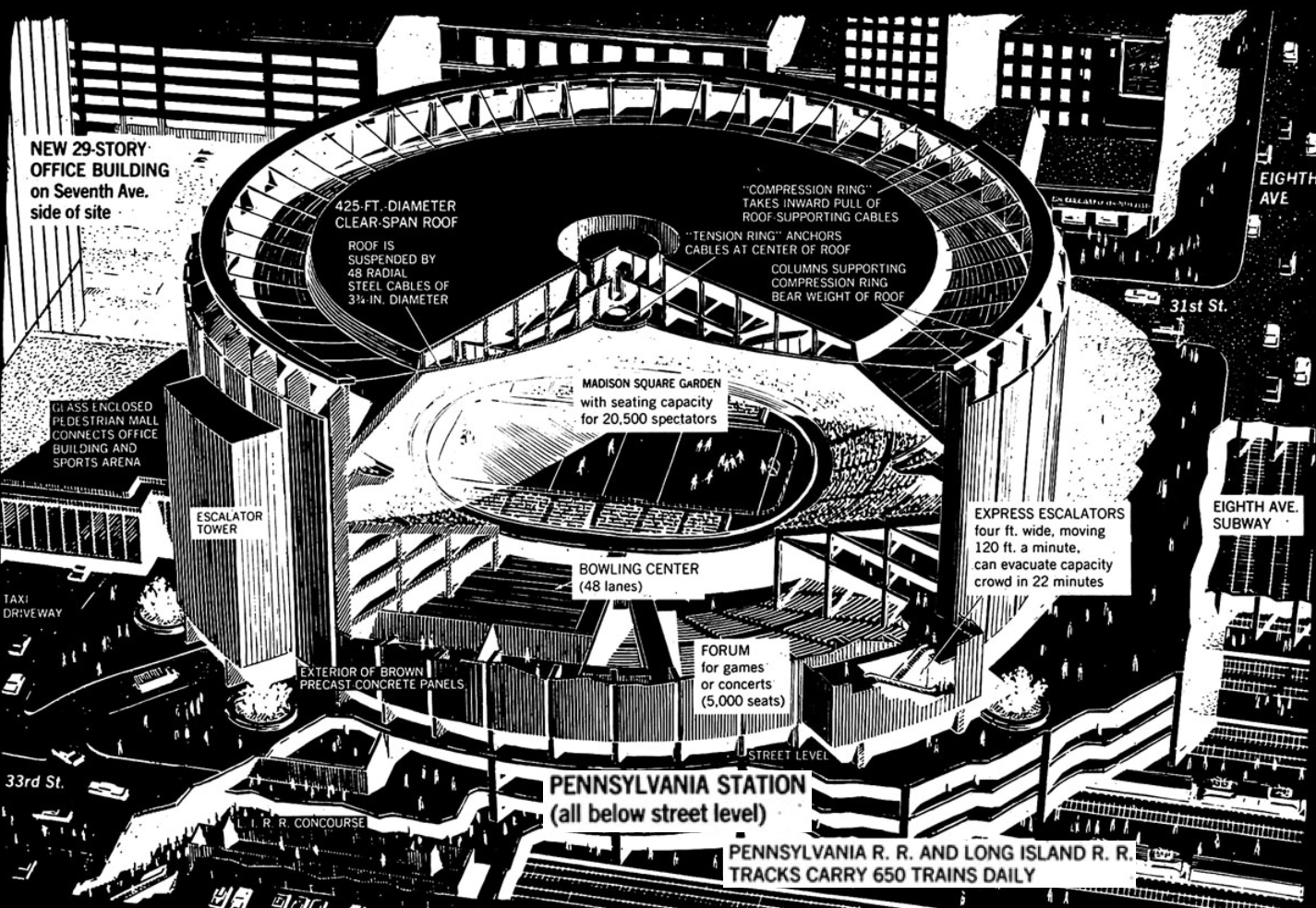

What is it about the black and white images of the original Penn Station that tickle the imagination of transit enthusiasts? Just the mention of Penn Station and some people begin waxing nostalgic about a place in which they’ve never actually stepped foot. We tend to forget that by the 1960s, Penn Station was falling apart, and rail travel was on the rapid decline. Still, this was no excuse to tear down a beaux-arts masterpiece. New York City needed a bold solution to address its changing transportation landscape, but also needed to preserve and restore its long-neglected, world-class train station. Instead, city leaders approved the construction of the current Madison Square Garden complex and the fate of the original Penn Station was sealed.

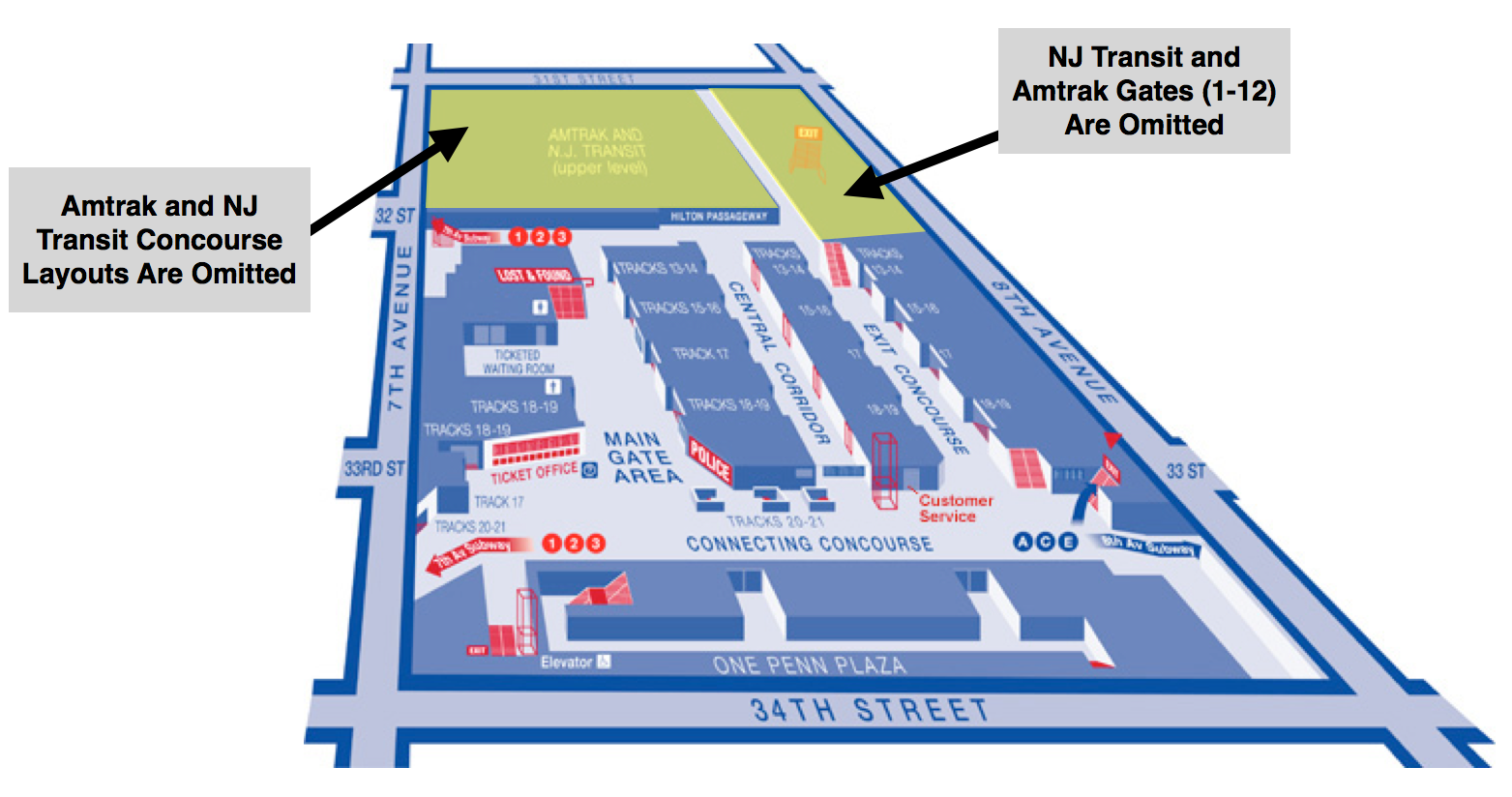

It turns out that rail travel didn’t go the way of the horse and carriage, and today, ridership is booming. Standing in the way of the region’s continued growth, however, is the current iteration of Penn Station, which continues to push the limits of its own operating capacity. Even though it serves twice as many daily passengers as Grand Central Terminal, Penn Station contains less than half as many tracks and platforms. In addition, scores of rail lines originating west of the Hudson River are forced to funnel single file through a pair of 100-year-old tunnels that opened with the original Penn Station. Worse still, simply getting around Penn Station remains a challenge for even seasoned commuters. Since Penn Station’s three rail systems (Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, and Long Island Rail Road) style and maintain their spaces independently, including their respective gate maps, unfamiliar travelers are often forced to aimlessly wander through unmarked corridors without the benefit of a unified station concourse.

So if we need a better, more efficient Penn Station, why don’t we just demolish the current station and build a new one? After all, during the 1960s, the city built the current Penn Station above its tracks and platforms without disrupting train service. The main reason why we can’t simply do it all over again is that this time around, Madison Square Garden needs to be razed first. Unfortunately, there are a number of fairly obvious reasons why the Garden’s owners, the Dolan family, have not yet caved to this suggestion. For starters, they own the property above Penn Station outright and use it (profitably) to operate the city’s premier sports and entertainment complex. In addition, the Garden is wrapping up a $1 billion renovation of its interior spaces, which the Dolans hope will ensure the Garden’s future competitiveness. Knocking down the Garden would also be sacrilege to generations of loyal Knicks and Rangers fans who have seen their franchises flourish in the current arena. Still, with the recent expiration of the Garden’s original fifty-year land-use permit, some city leaders have suggested using the Garden’s reapplication process as a bargaining chip to help pursue plans to rebuild a new Penn Station in the Garden’s place.

Manhattan borough president Scott Stringer has urged the City Council to issue a ten-year permit in order to allow the City to best prepare for its future transit needs. Stringer notes that while “we need to ensure the Garden always has a vibrant and accessible home in Manhattan, moving the arena is an important first step to improving Penn Station.” Similarly, the New Penn Station Alliance notes that a ten-year permit “would give the metropolitan region sufficient time to consider the best options for both Penn Station and Madison Square Garden, including a number of potential alternative locations for the arena within Manhattan.” Finally, the Department of City Planning has recommended that the Garden be given fifteen years instead of ten years, “because 10 years is too short and does not give the Garden enough [time] to relocate.”

While the Dolans have made it abundantly clear that they have no intention of relocating Madison Square Garden, even if the City Council voted to approve a ten or fifteen-year permit, it would still be decades of court battles and budget fights before a new Penn Station is finally planned, let alone built. The only immediate consequence of approving a temporary permit would be more uncertainty, more delays, and less action. This is not to say that the ongoing efforts to rebuild Penn Station should be abandoned at all. To the contrary, the abundance of existing infrastructure makes the question of rebuilding Penn Station less about if and more about when and how. But for the decades it may take to reach an ultimate solution, there may be other ways to tackle the problem. Thus, the bigger question to ask, and one that has not garnered enough attention over the past decade, is why city officials insist on focusing our near-term, transit-based planning around the Penn Station site when it comes with so much baggage.

The most obvious reason why city leaders have historically focused on Penn Station, as opposed to an alternative site, is that so many of the metropolitan region’s rail lines already converge at the Penn Station site. The very problem with focusing on Penn Station, however, is that once you commit to a site that is already built out, you are forced to work within its existing infrastructure. For instance, on the issue of train capacity, relocating Madison Square Garden would do nothing to expand Penn Station’s underlying footprint in order to allow for the construction of new tracks and platforms. Rebuilding Penn Station may unify and enlarge its concourse space, but it would not ease the train traffic traveling in and out of the station every day. The city should be looking for ways to increase track and platform capacity first and make station improvements later. In addition, if a primary goal is to increase overall capacity in and out of Manhattan, a secondary goal should be to diversify the location of our transit resources in order to allow passengers to more efficiently reach their ultimate destinations. This idea is already being implemented by the MTA with the construction of the East Side Access project, which will for the first time provide Long Island Rail Road trains the option of terminating in Grand Central Terminal. Rebuilding the Penn Station site, as opposed to exploring alternative locations, will ensure that NJ Transit commuters and Amtrak riders will continue to have only one direct route into the largest city in the nation.

A number of alternative plans seeking to overhaul the Penn Station site also miss the mark in terms of comprehensively addressing our broad-based transit challenges. The current Moynihan Station proposal, for instance, will help to alleviate passenger crowding by opening up new concourse space, but does nothing to remedy the inadequate cross-Hudson train capacity. As bluntly put by former Amtrak president David Gunn, “[f]rom a transportation point of view, [Moynihan Station] makes no sense.” In addition, Amtrak’s Gateway Program, which seeks to construct two new cross-Hudson rail tunnels, fails to address Penn Station’s existing inadequacies and only provides minimal increases to train capacity. Moving forward, while politicians figure out how to tackle the various obstacles to rebuilding Penn Station, city planners should, at the same time, be looking to alternative sites for the expansion of our commuter and regional rail services in order to maximize the benefits of every public dollar spent.

Plans to invest significant public funds into the current Penn Station site also fail to recognize the reality of the New York real estate market. Since the completion of Madison Square Garden and Penn Plaza in the late 1960s and early 1970s, new construction in the vicinity of Penn Station has been virtually nonexistent. Most recently, the proposed 15 Penn Plaza real estate development, a super-tall skyscraper complex that was set to reinvigorate the neighborhood adjacent to Penn Station, was scrapped after years of planning. Not far from Penn Station, however, neighborhoods like the Hudson Yards, West Chelsea, and Lower Manhattan are emerging with new and dynamic real estate developments. Comprehensive proposals should look to real estate markets that are growing, as opposed to stagnating, in order to supplement traditional financing sources through transit-oriented developments.

If we are looking to make real progress over the next several years, as opposed to the next several decades, we need to stop focusing exclusively on those transit proposals that rely on Madison Square Garden abandoning its iconic home for the last fifty years in order to succeed. Of course it would be great if the Dolans were on board with a plan to rebuild Penn Station, and one day, there will be a new, modern station where Madison Square Garden currently stands. But today, the Dolans are not on board, and there is no reason to think that they will reverse their position in the near future. We’ve tried this course for the last twenty years and it is time to move on before another decade passes without a concrete plan. Instead of wishing for the day when the Penn Station of 1910 is rebuilt in all its former glory, we should be looking for alternative transit proposals that take advantage of alternative locations within the city to tackle problems that are currently unsolvable within the existing Penn Station infrastructure. New York not only needs, but deserves a new world-class train station. But if that station is going to be built for the current generation of riders, instead of the next one, it may be time to start scouting other locations for Manhattan’s next great transit hub.