Alternative Proposals

Part of the reason why the Hudson Terminal Plan is favorable to the current alternative proposals is that it is focused on maximizing results for the New York metropolitan region as a whole, as opposed to picking favorites by agency. For instance, Amtrak’s Gateway Project puts the majority of its resources towards furthering the federal goal of upgrading the Northeast Corridor for future high-speed rail. Or the MTA’s 7-Line Subway Extension to Secaucus proposal heavily favors New York City’s mass transit infrastructure, but does nothing to improve cross-Hudson commuter rail capacity. As discussed in this section, by allocating resources inefficiently, not only are these proposals’ final designs ineffective at addressing the region’s transportation problems, but the visions proposed are shortsighted and costly.

Amtrak’s Gateway Project

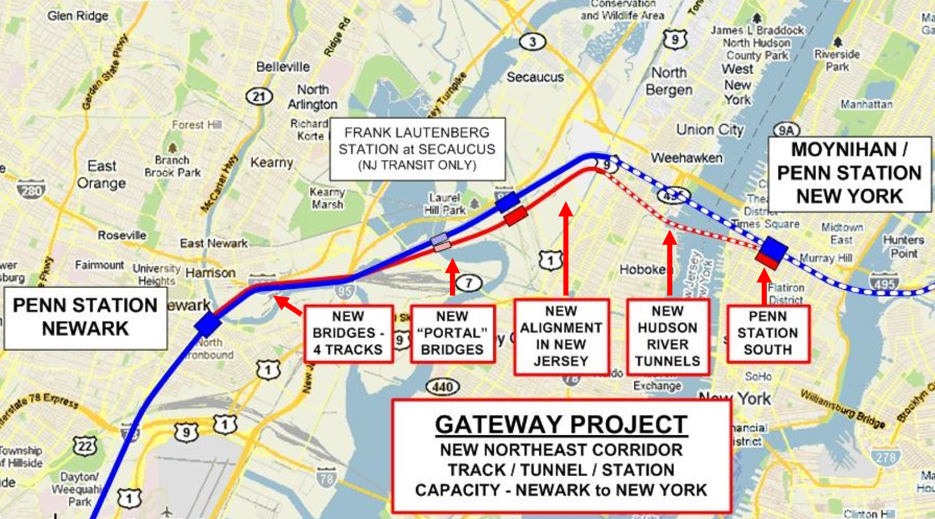

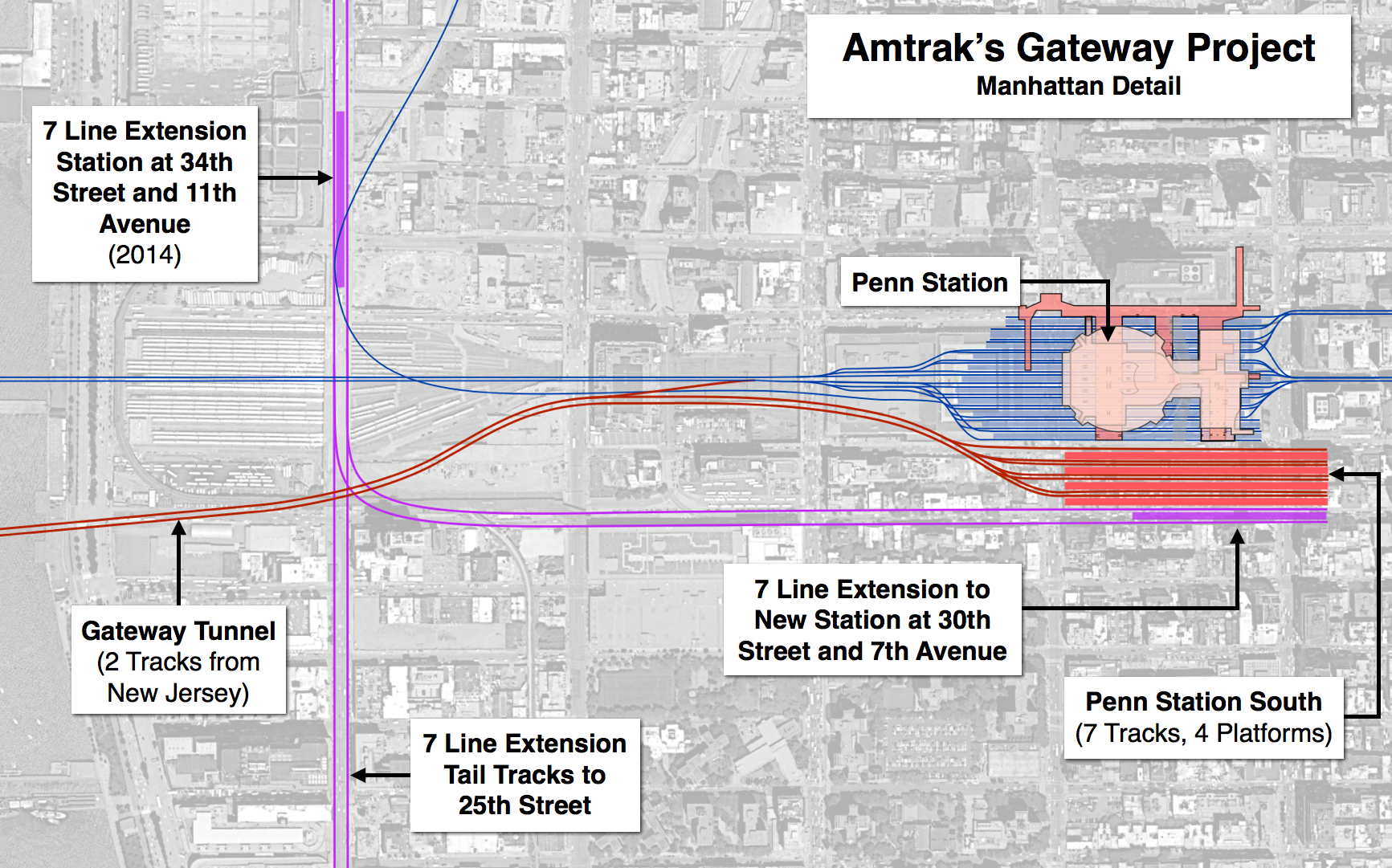

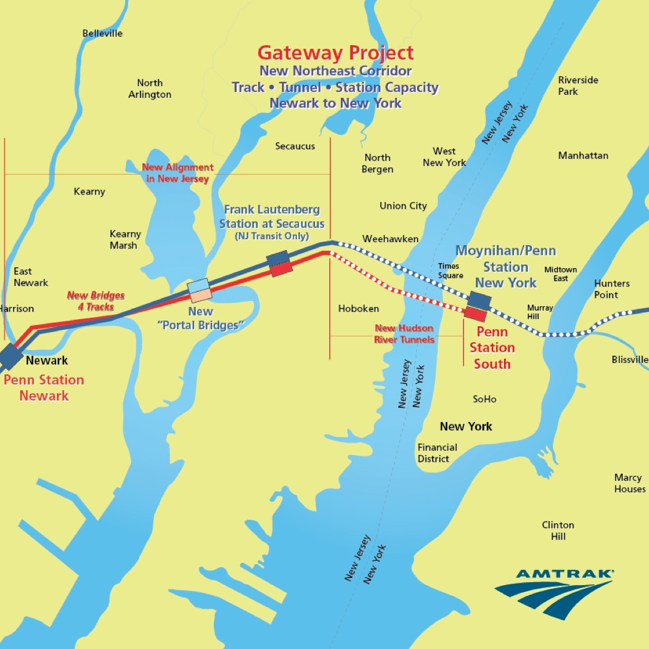

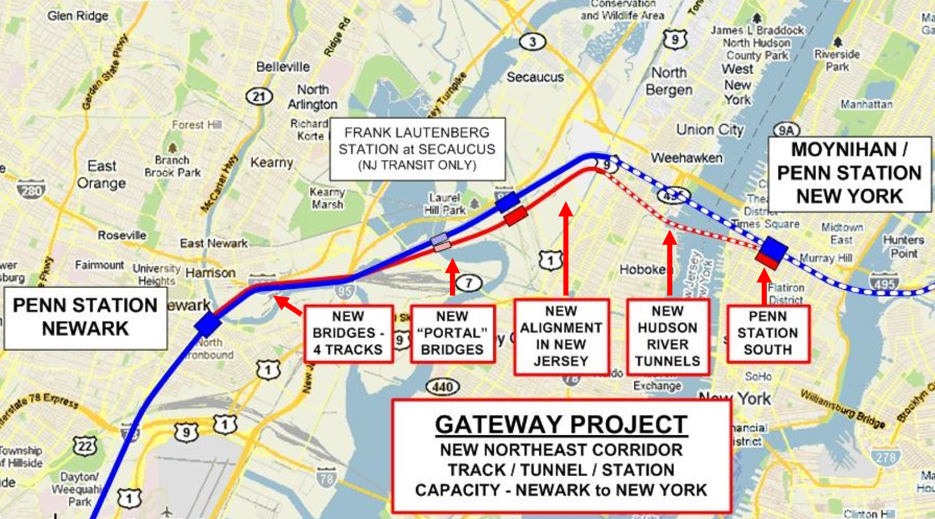

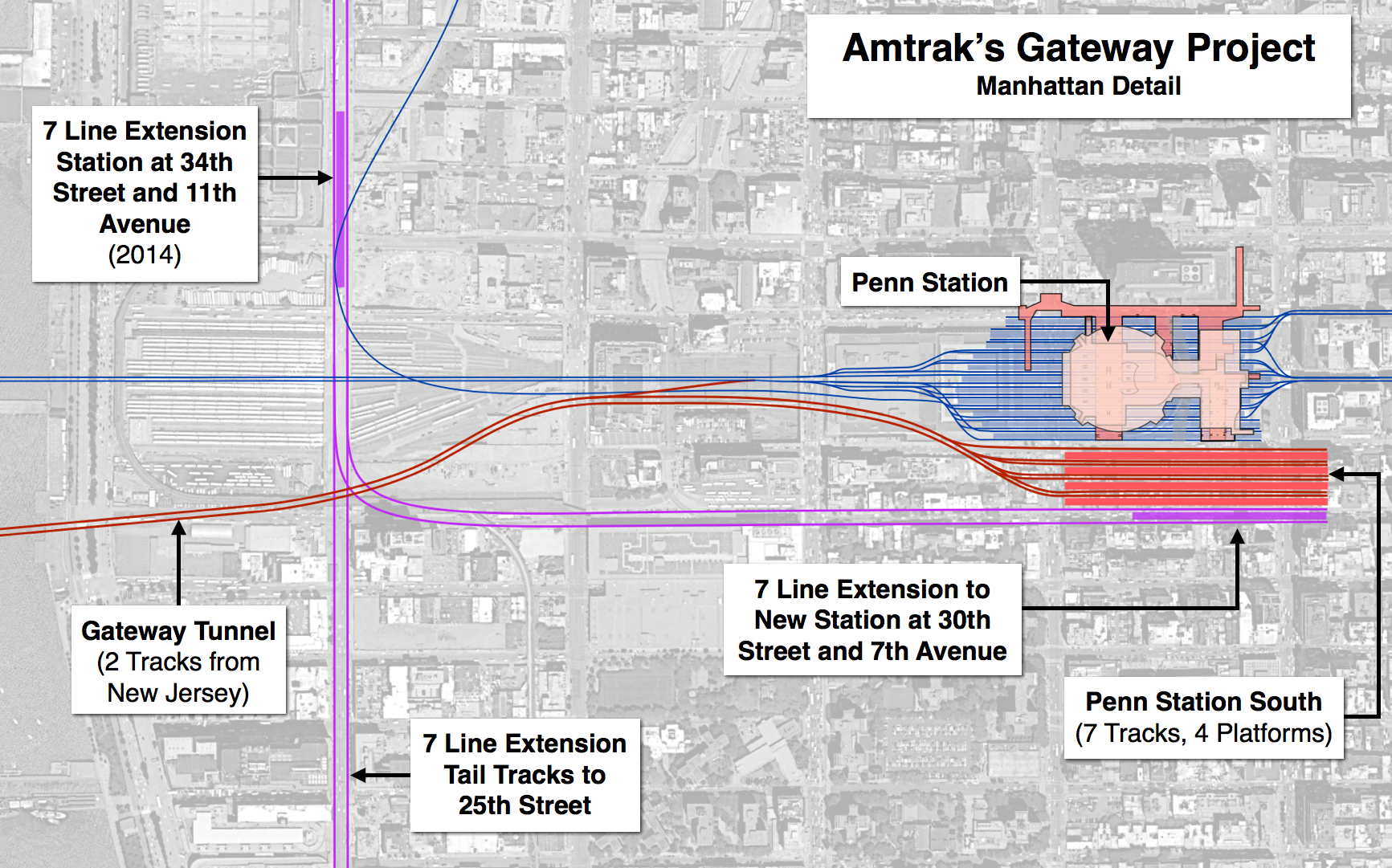

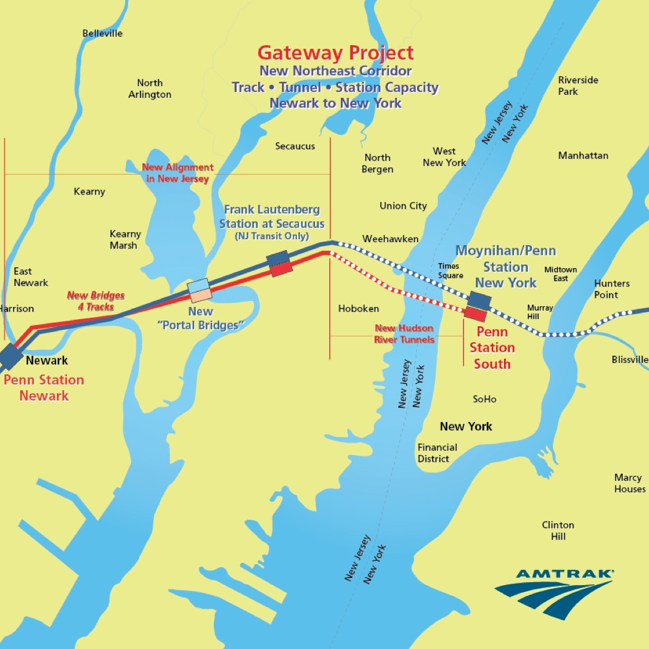

The Gateway Project consists of over 10 miles of new trackage from Newark to Manhattan. Included within this trackage are two new high-level, two-track portal bridges over the Hackensack River, which would connect to the already-built, four-track Secaucus Junction. Upon leaving Secaucus Junction, two tracks along a new alignment would travel east towards two new single-track tunnels passing under Bergen Hill towards Penn Station. Upon arriving into Manhattan, the two new tunnels would merge with trackage heading into Penn Station before ultimately terminating at a four-platform, seven-track annex station called Penn Station South. The Gateway Project also calls for an extension of the 7-Line from 34th Street and 11th Avenue to a new station at 30th Street and 7th Avenue, which would connect to the new Penn Station South annex. There have not been any feasibility studies completed at this time, but preliminary estimates put the total cost of the project at $14.5 billion with a completion year of 2025.

Gateway Project Route from Amtrak’s Presentation Materials

While the Gateway Project may, on its face, appear to address New York’s transportation woes, in actuality, it suffers from numerous deficiencies. The most obvious of these deficiencies is the enormous expense compared with the minimal benefit provided to residents of the New York metropolitan region. The Gateway Project requires over 10 miles of new trackage to bring a total of just two new tracks into Manhattan across the Hudson River. The Hudson Terminal Plan, by contrast, takes advantage of existing rail infrastructure and accomplishes the same feat with just 4,100 feet of new trackage—the distance from Hoboken to the western banks of Manhattan. In addition, it is unclear whether the $14.5 billion estimate includes the 3,700 feet of new subway tunnel and new subway station at Penn Station South. Using price comparison methods, this extension alone would cost an additional $1.2 billion. Since it would be significantly faster to reach destinations such as Times Square, Bryant Park, and Grand Central Terminal by using current subway lines near Penn Station, this $1.2 billion extension would essentially act as a five-block link for only those commuters traveling from Penn Station to the Hudson Yards. Depending on the frequency of service, it may ultimately prove faster and more convenient to walk from Penn Station’s northwest exit to the Hudson Yards. Given the large costs and small population served, the proposed extension of the 7-Line to Penn Station South represents a reckless exercise in city planning by Amtrak. Finally, despite 10 miles of proposed new trackage, the Gateway Project lacks a vital rail link to Manhattan for passengers traveling along the Main Line, Bergen County Line, and Pascack Valley Line. This connection would, for the first time, provide passengers along these lines a one-seat ride into Manhattan at relatively minimal costs.

Amtrak’s Gateway Project also fails to fix the fundamental flaws with Penn Station’s design. Penn Station South neither contains a unified, central concourse nor open air spaces—two vital components of a successful transit hub. Instead, the Gateway Project does the opposite. It creates an additional disjointed space deep below the street level. In essence, Penn Station South annexes a basement to the basement that is Penn Station. Even if Penn Station South incorporated these necessary design elements, the Gateway Project still requires the demolition of scores of private buildings and residences within two midtown blocks on the site of the station. Among the 330 small businesses and 220 residents requiring relocation, Amtrak plans to raze the Blarney Stone, an Irish pub on 8th Avenue that has been serving locals and sports fans from Madison Square Garden for more than 50 years, and the Roman Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist, founded in 1840. As seen by the ongoing litigation involved with the construction of the Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn, eminent domain battles take significant time and financial resources to fight, and threaten projects from getting off the ground at all.

The Gateway Project also fails to reform the bureaucratic and political hierarchy in Penn Station’s oversight and financing. As Amtrak’s operating losses continue to run over $1.2 billion annually, instead of reforming its holdings and reorganizing its bureaucracy, Amtrak plans on expanding its operations in the New York metropolitan region. As Amtrak expands its high-speed rail network and annual passenger volume continues to rise, it may be forced to use more and more trackage within Penn Station, a move it would be entitled to do as its owner. And despite billing Penn Station South and the Gateway Project as a transformative plan for New York City transit, it is unclear why Amtrak would not look to Penn Station South as another tentpole for its losses in the same way it has done with Penn Station. New York City residents and commuters alike have seen for decades that Amtrak is not the landlord it wants running its primary transit hub in the future.

Gateway Project Map from Amtrak's Presentation Materials

Lastly, and perhaps most disappointingly, despite its large cost, the Gateway project does little to drastically reduce Penn Station’s capacity constraints. As stated earlier, over the past 35 years, the number of daily trains in and out of Penn Station has increased by approximately 90%. At the same time, total population in the New York metropolitan region has increased by only 13%, from 16.2 million people in 1970 to 18.4 million people in 2010. It is clear that rail use by the metropolitan population is increasing at a much greater rate than general population growth. As gas prices continue to rise and the public chooses commuter rail in greater and greater numbers, it would not be unreasonable to see rail usage double again in the next 35 years. Despite the expected growth of this mode of transportation, Amtrak has proposed increasing Penn Station hourly train capacity by a mere 48%, from 62 total trains per hour to 92 total trains per hour. Perhaps this increase would serve the at-capacity demand for rail travel already plaguing the system. But if demand for rail travel continues to grow at the current pace, the Gateway Project, which is scheduled to be finished by 2025, will be inadequate upon its completion and Penn Station will remain a choke point for the entire system.

However, even if NJ Transit was able to fulfill the increased hourly train capacity maximums, it would have to greatly increase its service, requiring the purchase of new rolling stock, building of new train yards, hiring of new conductors and maintenance workers, and renting additional trackage from Amtrak’s Penn Station South. Given that NJ Transit has operated at an average annual loss of over $1.4 billion for the past three years, it is unclear how the New Jersey transportation budget would be able to absorb the broad expansion of rail service needed to utilize the improvements from the Gateway Project. By contrast, the Hudson Terminal Plan takes advantage of the nearly 300 daily trains that already travel to and from Hoboken, but that are currently underused due to their termination in New Jersey.

Even though cross-Hudson capacity would increase under the Gateway Project, albeit minimally, Penn Station would still only be left with a total of 28 tracks and 15 platforms to service 1,250 daily trains. By comparison, Grand Central Terminal services 572 daily trains with 44 tracks and 26 platforms. The current problems associated with delay in Penn Station are largely caused by the lack of train capacity within the station. Had Amtrak truly wished to provide a permanent solution to Penn Station's constraints, it would have included more than just 7 new tracks over 4 platforms.

No large-scale transit proposal will ever be perfect and every plan will contain tradeoffs to attain desired goals. However, the Gateway Project does not even attempt to tackle the complex transit problems that have afflicted New York and New Jersey residents for decades. The Gateway Project is neither bold nor imaginative, and does more to maintain the status quo than it does to prepare New York City for the next great wave of transportation infrastructure. By contrast, for half the total cost of the Gateway Project, the Hudson Terminal Plan will provide double the cross-Hudson rail capacity, a premiere new transit hub on the banks of the Hudson River, and sensible mass transit improvements to promote the growth of Manhattan’s West Side and the metropolitan region as a whole.

Next: Access to the Region’s Core...