Table of Contents

Download Planning for a New Northeast Corridor:

Download The Hudson Terminal Plan:

Download the Trends & Opportunities Report:

Capturing Value Through Transit-Oriented Development

Transit-Oriented Development (“TOD”) involves the strategic and often mutually-beneficial construction or redevelopment of mixed-use properties in the immediate vicinity of a transportation infrastructure project. Successful TODs add value to a given public transportation project by not only encouraging new ridership, but also catalyzing economic development. To that end, where transit projects have difficulty securing funding through traditional methods, a comprehensive TOD plan may assist in raising capital by leveraging future development revenues in exchange for financing. Government agencies traditionally help to implement successful TODs through the imposition of district-specific zoning changes, issuance of bonds, and utilization of a number of strategic value capture mechanisms.

The Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project

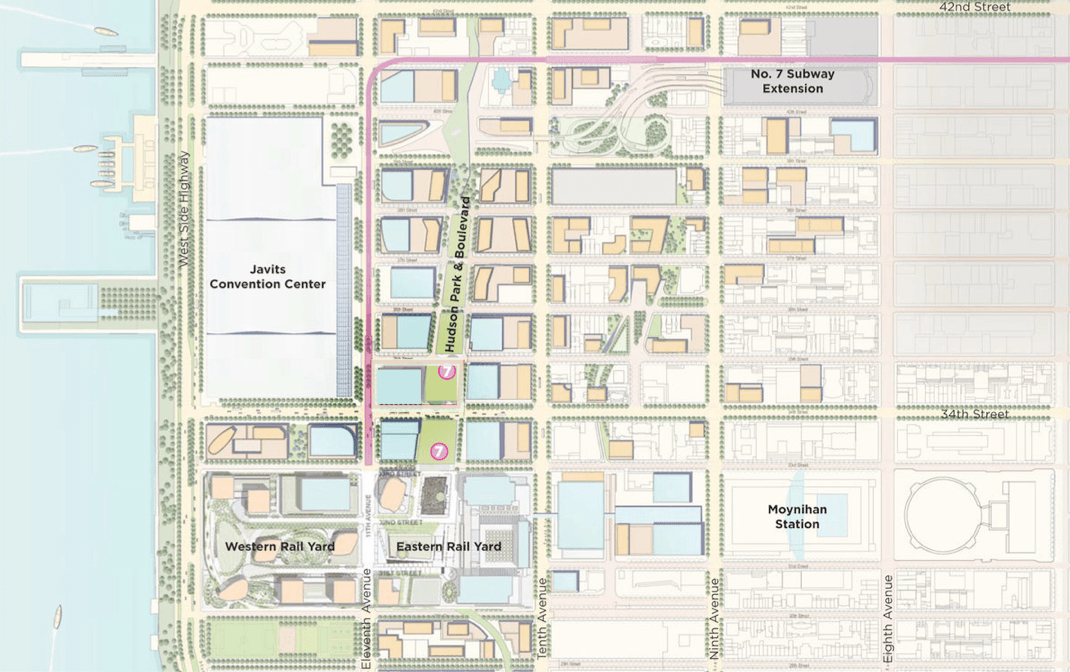

In New York, one of the most prominent examples of the mutually beneficial relationship between transportation improvements and TOD is the Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project (“HYRP”). In the early 2000s, and in conjunction with a bid to host the 2012 Olympics, the City of New York proposed extending the 7-Line Subway to Manhattan’s West Side at 34th Street and 11th Avenue and redeveloping the adjacent, underdeveloped areas. However, despite the City’s advocacy for the project, the MTA (a state agency) had already prioritized funding for other transit projects including the LIRR’s East Side Access and Second Avenue Subway. Viewing the 7-Line Subway Extension as an opportunity to catalyze economic development along Manhattan’s West Side, the Bloomberg Administration sought to fund the transportation project independently of the MTA by leveraging future TOD revenues in exchange for financing. The first step towards achieving this goal involved rezoning 45-blocks of mostly manufacturing space in the vicinity of the 7-Line Subway Extension to accommodate significant increases in commercial and residential development. This zoning amendment allowed for the creation of 25.8 million square-feet of commercial space, 20,000 residential units, two million square-feet of hotel space, one million square-feet of retail space, and 20 acres of parks and open space, including the ten-block Hudson Park and Boulevard in between 10th and 11th Avenues.

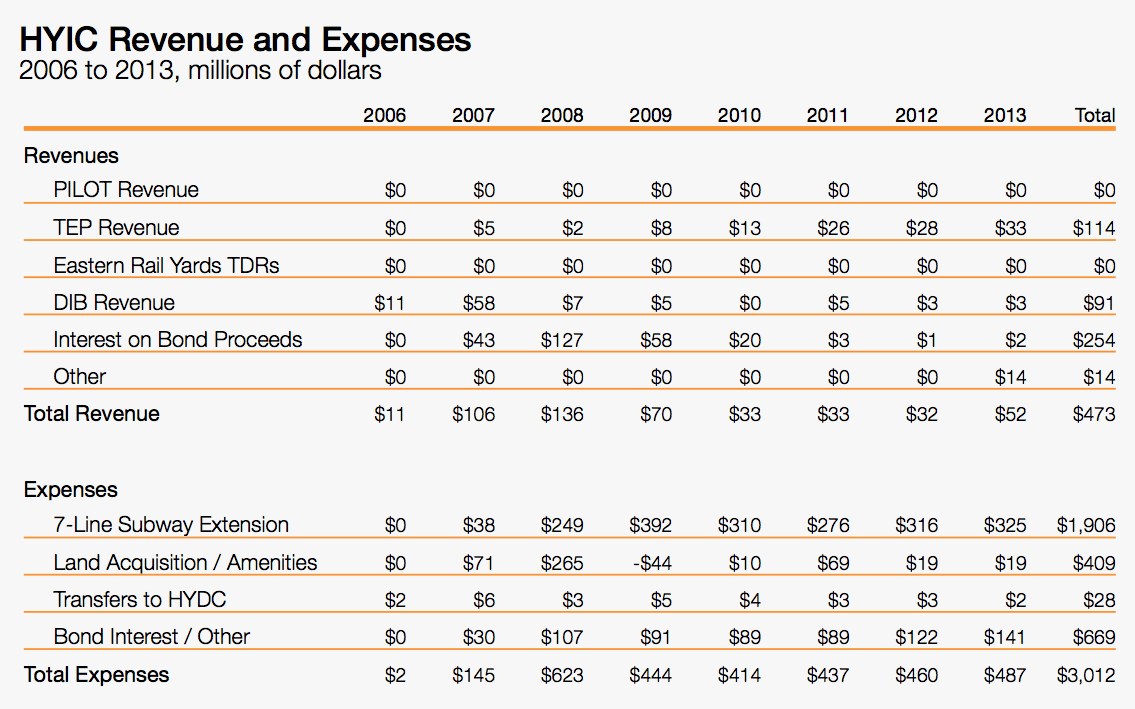

In order to facilitate the HYRP, the City of New York created the Hudson Yards Development Corporation (“HYDC”) to manage the planning, design, and development of the project area, not including the actual 7-Line Subway Extension, which would be managed by the MTA. The City also created the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (“HYIC”) to finance the capital improvements required to implement the HYRP. Since 2007, the HYIC has raised $3 billion in proceeds from two bond offerings. In order to secure and repay these bonds, the HYIC and HYDC put forth several means of capturing the added value of the new real estate developments under the HYRP. The largest source of revenue is set to come from commercial payments in lieu of taxes (“PILOTs”). Under a PILOT arrangement, the New York City Industrial Development Agency (“NYIDA”) would purchase the land to be developed from a commercial developer for a nominal amount, which would in turn relieve the developer from paying traditional property taxes. Thereafter, over the course of the next 30 years, the developer would pay a determined price per square foot to the NYIDA, who would then transfer those proceeds to the HYIC. At the end of the 30 years, the property would be sold back to the developer for a nominal price and the developer would resume paying normal property taxes. In order to incentivize new developments prior to the build-out of the master plan site, the NYIDA was empowered by the City to discount the PILOT rates below normal property tax rates depending on location and completion date of a development. For those developers who opt out of the PILOT program, the City of New York has agreed to repay the HYIC all property taxes received from properties constructed after 2005 in the form of Tax Equivalency Payments (“TEPs”).

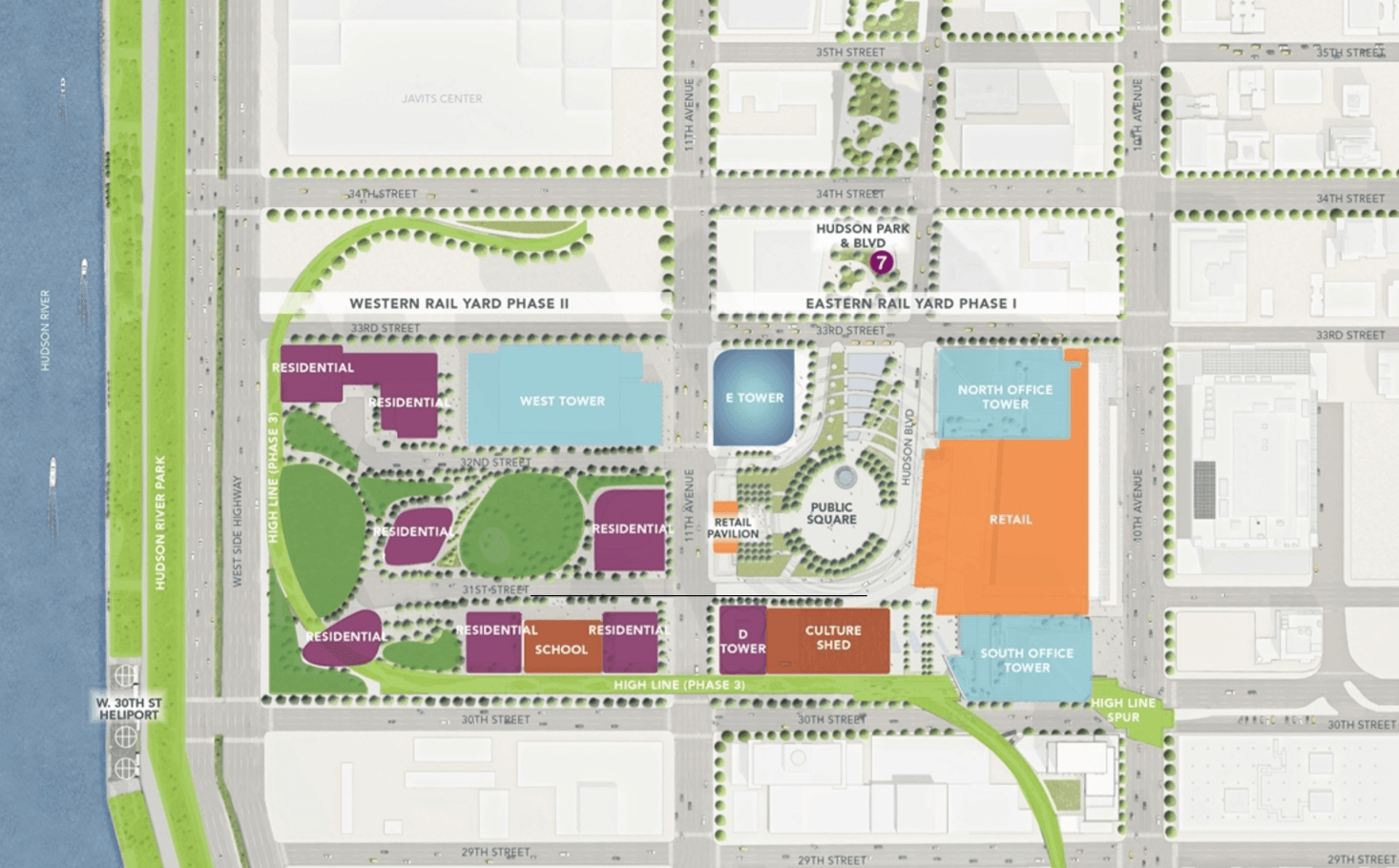

Another source of revenue for the HYIC will come from the sale of various transferrable development rights (“TDRs”) tied to the development of the eastern half of the MTA’s West Side Yard (the “Eastern Rail Yard”). Developers are traditionally allowed to build, as-of-right, a structure with a maximum total floor area determined by multiplying the lot size by the zoned floor-area ratio (“FAR”) for the given lot. For instance, a developer looking to build an office tower on a 10,000 square-foot lot with a zoned FAR of 6 can construct, as-of-right, a 60,000 square foot building. The City’s HYRP zoning changes increased the as-of-right and maximum FARs within the Eastern Rail Yard to allow for the construction of 10.8 million square feet of new mixed-use space. However, since the HYRP requires the incorporation of parks, public plazas, and other non-commercial elements throughout the project site that restrict maximum development, the MTA was only able to lease 5.1 million square-feet of development rights over the Eastern Rail Yard, which is also set to raise over $1 billion in rental payments over the 99-year term of the lease. In 2007, the HYIC purchased from the MTA a 50% interest in over 4.5 million square-feet of TDRs from the unusable space over the Eastern Rail Yard for $200 million. Hudson Yards developers wishing to increase a given property’s FAR may purchase these TDRs, of which the proceeds will go to the HYIC until it recoups its initial $200 million investment plus interest. After that point, the proceeds from sale of these TDRs will then go to the MTA. Developers may also increase their FAR through the purchase of District Improvement Bonuses (“DIBs”) from the HYIC, which function in a similar manner to the Eastern Rail Yard’s TDRs. While they are priced somewhat differently, today, TDRs and DIBs may be purchased for approximately $125 per additional square-foot.

The HYIC has yet to capitalize on most of its value capture mechanisms, including PILOT and TDR revenue, because very few eligible projects have begun construction, and those that have begun construction will not be completed (and thus generate revenue) for several years. The HYIC has, however, raised over $200 million in TEP and DIB revenue since 2006 on developments that were completed during the earlier stages of the HYRP. Through 2013, the HYIC has spent nearly $2 billion on the 7-Line Subway Extension, which has been funded chiefly by the HYIC’s two bond issuances that raised $3 billion. The HYIC has also spent over $400 million in land acquisition and public amenity construction in order to implement various elements of the HYRP, including the construction of Hudson Park and Boulevard as well as other public spaces. As the 7-Line Subway Extension wraps up and the first large-scale developments open in the upcoming years, the HYIC will begin taking in increasing revenues, which will allow them to repurchase their bonds and fully implement the HYRP. Because of the strategic partnership between transportation infrastructure improvements and real estate development, the HYRP has not only helped to facilitate the construction of an expensive transit project, but will also increase ridership, create a new livable and workable district in a previously depressed area of Manhattan, and catalyze economic development.

Other Methods of Capturing Added Value from TODs

There are a number of other ways in which government agencies charged with developing TODs are able to capture the added value created by new transportation infrastructure projects. One of the most common strategies is through the assessment of district-specific taxes on properties directly benefiting from a transportation infrastructure project, which operate similarly to PILOT agreements. One recent example of the utilization of special district assessment taxes was the construction of the Washington Metro’s NoMa – Gallaudet U Station in 2004. As part of the project’s financing, private landowners set to benefit from the station’s construction agreed to pay a special assessment tax over 30 years to raise $25 million of the $100 million total project cost. This special assessment tax will be charged on top of regular property taxes for nonresidential parcels located within 2,500 feet of the future station’s entrances. The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority financed the project, in part, by issuing bonds that will be repaid using the funds collected through the special assessment tax over the subsequent decades.

Another method of capturing value from TODs is through Tax Increment Financing (“TIF”), which involves promising future tax revenues to secure present financing arrangements. Since infrastructure improvements increase property values, which results in higher tax revenues, government agencies are able to leverage those future revenues through TIF proposals in order to finance a given infrastructure project. For example, as part of its $488 million redevelopment of Denver Union Station, the Denver Union Station Project Authority (“DUSPA”) obtained a $155 million, 3.91%, 30-year loan from the Federal Railroad Administration’s Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (“RRIF”) program, which operates similarly to the US DOT’s TIFIA program. In order to secure and pay for the RRIF loan, the Denver Downtown Development Authority, which oversees TOD within the 40-acre project site, agreed to appropriate all tax increment revenue over the next 30 years to DUSPA. Because TIF relies on predicting future tax revenue, the City and County of Denver agreed to appropriate up to $8 million annually during the term of the RRIF loan to cover any potential shortfalls in tax increment revenues.

Another popular method of capturing added value is through public-private joint ventures. Since transit agencies often lack the expertise and resources to develop certain aspects of TODs on their own, they may enter into joint development agreements with private partners to construct TODs on publicly-owned land. For the HYRP, this involved the leasing of the publicly-owned Eastern Rail Yard to a joint venture between the Related Companies and Oxford Properties. In another example, funding for the 2011 construction of the West Dublin/Pleasanton infill commuter station outside of San Francisco was achieved through a public-private partnership between Bay Area Rapid Transit (“BART”) and private developers. Under the arrangement, the private developers prepaid $15 million of the $100 million project cost for a ground-lease to develop a transit village on three acres of government-owned land adjacent to the new station. In addition to this one-time payment, the developers also agreed to pay BART a fee for every sale of residential units within the development, which would allow BART to continue to capture value from its new station.

Public-private partnerships may also be used in instances where the sale or lease of public land is not available. Private investment can be leveraged where public entities engage in risk-mitigation of private developments through environmental remediation, entitlement and construction risk mitigation, financing assistance, and marketing of a given TOD. In Dallas, for instance, the Dallas Area Rapid Transit Authority (“DART”) engages developers by providing market analyses for transit projects, which in turn reduces predevelopment costs. In another example from the late-1990s, the City of Portland negotiated with the owner of a 40-acre parcel of land adjacent to the proposed alignment of a new streetcar extension in order to increase the minimum construction density of residential and commercial development within the project site in exchange for bringing the streetcar past the owner’s property and making other area improvements. Almost 20-years later, the neighborhood around the TOD is today one of the most popular areas in the city and, at build-out, will be home to 10,000 residents and over 20,000 jobs. The success of this public-private partnership has led to the expansion of the streetcar system in Portland and creation of new, more extensive joint TOD ventures.

TOD and the New Northeast Corridor

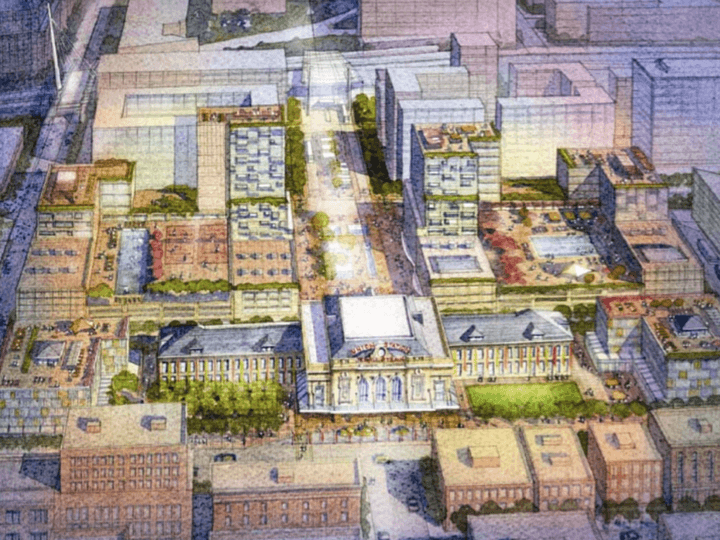

The proposed improvements to the Northeast Corridor provide significant opportunities for strategic TODs to increase ridership, drive economic development, and catalyze financing for a given segment of the overall project. For the southern section of the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak is already implementing its 20-year plan to redevelop Washington Union Station. In 2006, Akridge, the lead private developer behind the real estate elements of the project, purchased from Amtrak the air rights to construct over three million square-feet of mixed use space above the existing rail yards behind Washington Union Station. While funding sources for Amtrak’s $7 billion master plan are still to be determined, it is crucial that Amtrak leverage the added value of its master plan in financing the project.

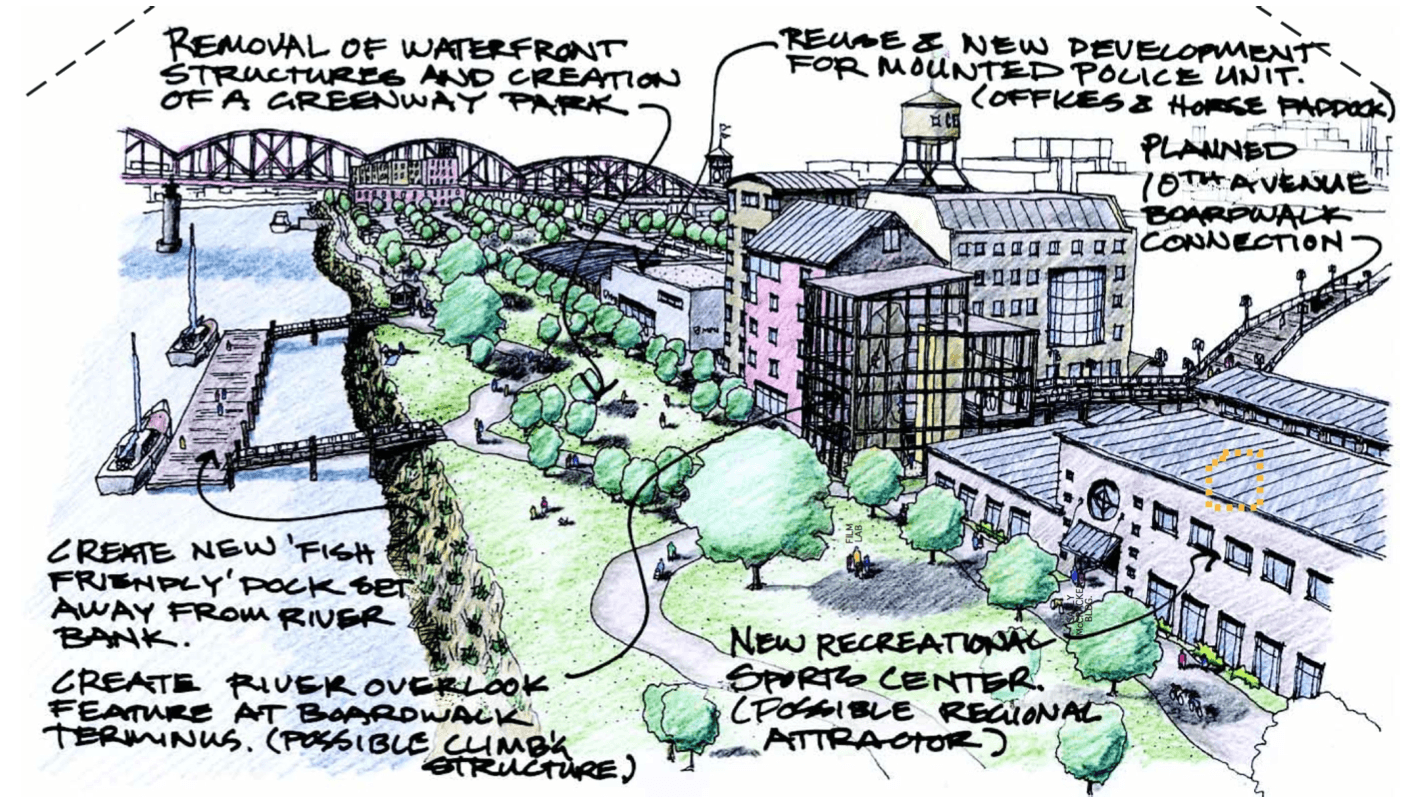

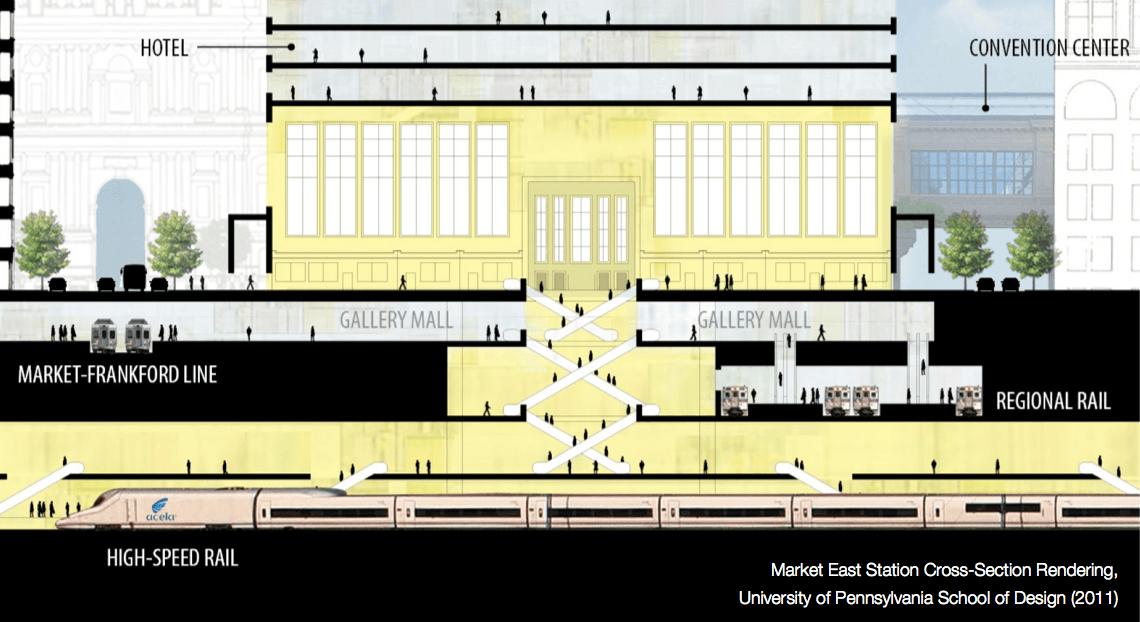

For the remaining stations throughout the southern section of the Northeast Corridor, TOD plans should promote smart real estate development that contributes to a dense urban environment with an eclectic mix of uses built around a diversity of transit options. In Baltimore, the construction of a downtown Charles Center Station will bring high-speed rail to an already bustling city center. However, there still remain opportunities for infill development in low-density lots and blighted buildings within walking distance of the new station. A successful TOD plan in Baltimore should involve rezoning these areas for higher-density development and utilize value capture mechanisms such as TDRs and DIBs to help finance the construction of the station structure. Similarly, in Philadelphia, a new Market East Station will benefit most from its extensive connections to numerous transit lines within an already built-out city center. Nevertheless, there still remains significant redevelopment potential around sites such as the Philadelphia Convention Center, Reading Terminal Market, Independence Mall, and the Market Street Corridor. A successful TOD plan in Philadelphia should focus on ensuring the efficient connectivity of the city’s various transit systems as well as improving public spaces to encourage new development and increase ridership. In addition to these hub stations, there are a number of TOD plans already being implemented at intermediate stations along the southern section of the Northeast Corridor. For example, in Trenton, the Downtown Capital District Master Plan proposes a $73 million upgrade to Trenton Station as well as enhancements to the adjacent light-rail River LINE station, construction of new public spaces and parks, and development of a large-scale transit village adjacent to the station. Funding for the Trenton plan will be secured, in part, by the New Jersey Department of Transportation’s Transit Village Grant Program meant to assist municipalities in financing new TODs.

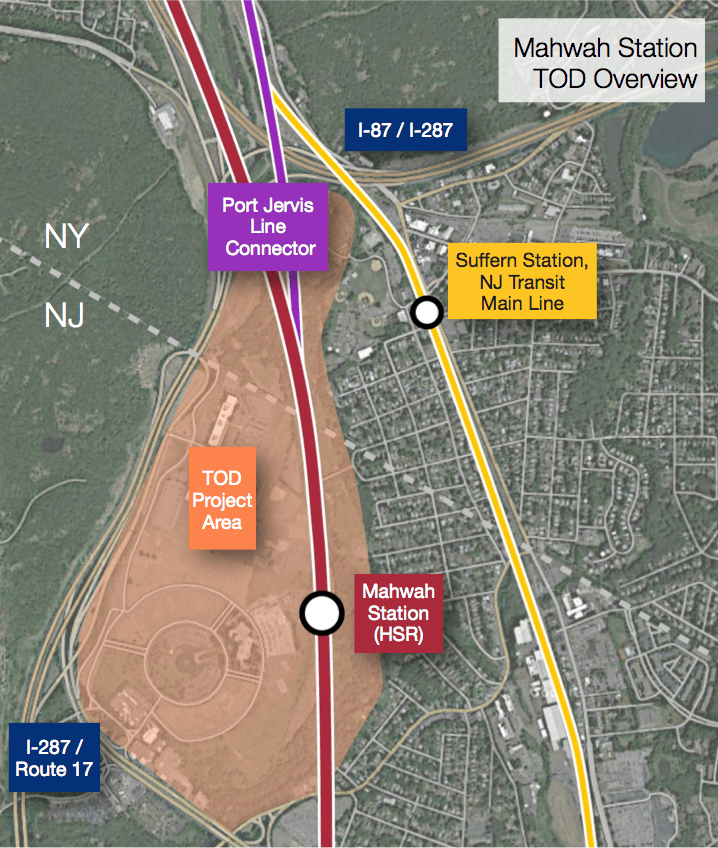

Unlike the southern section of the Northeast Corridor, the northern section of the new Northeast Corridor will be constructed along a new alignment traversing several markets without current access to express, intercity passenger rail, thus allowing for extensive TODs. For instance, In Mahwah, NJ, a new high-speed rail station will be built next to over 200- acres of underdeveloped land currently situated in between Interstate-87/287, Route 17, and the Ramapo River. This strategically located development site, which already contains a Sheraton Hotel, would allow for large-scale TOD to include a commuter village with park- and-ride facilities, an intermodal bus station, and new commercial and retail space. Since this site is largely undeveloped, managing agencies will be able to take advantage of numerous value capture mechanisms to generate significant revenues and incentivize investment within the project site.

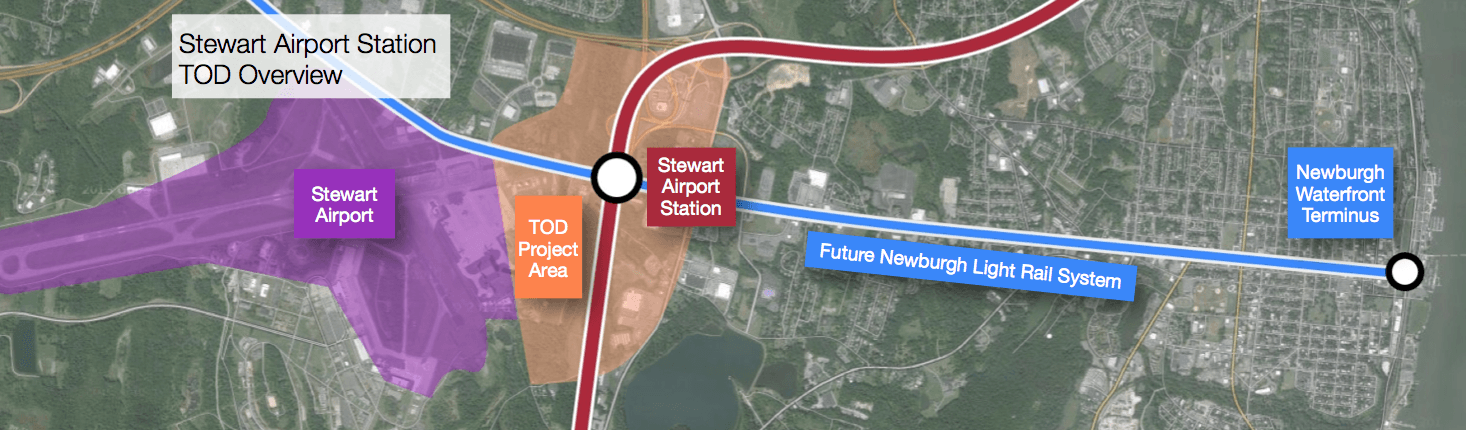

In Newburgh, TODs around the Stewart Airport Station will serve to revitalize the city through strategic development over a 1.25 square-mile project area bordered by Interstate-84, Interstate-87, Stewart Airport, and a future light rail link to the downtown Newburgh waterfront. Like Mahwah Station, Stewart Airport Station will serve as a transit village for metropolitan workers living in upstate New York. Due to the State of New York’s interests in stimulating the long- depressed Newburgh economy and improving transit for upstate residents, as well as the Port Authority’s interest in improving access to and increasing ridership within Stewart Airport, the Stewart Airport Station TOD will also be able to take advantage of numerous value capture mechanisms to help fund rail infrastructure improvements.

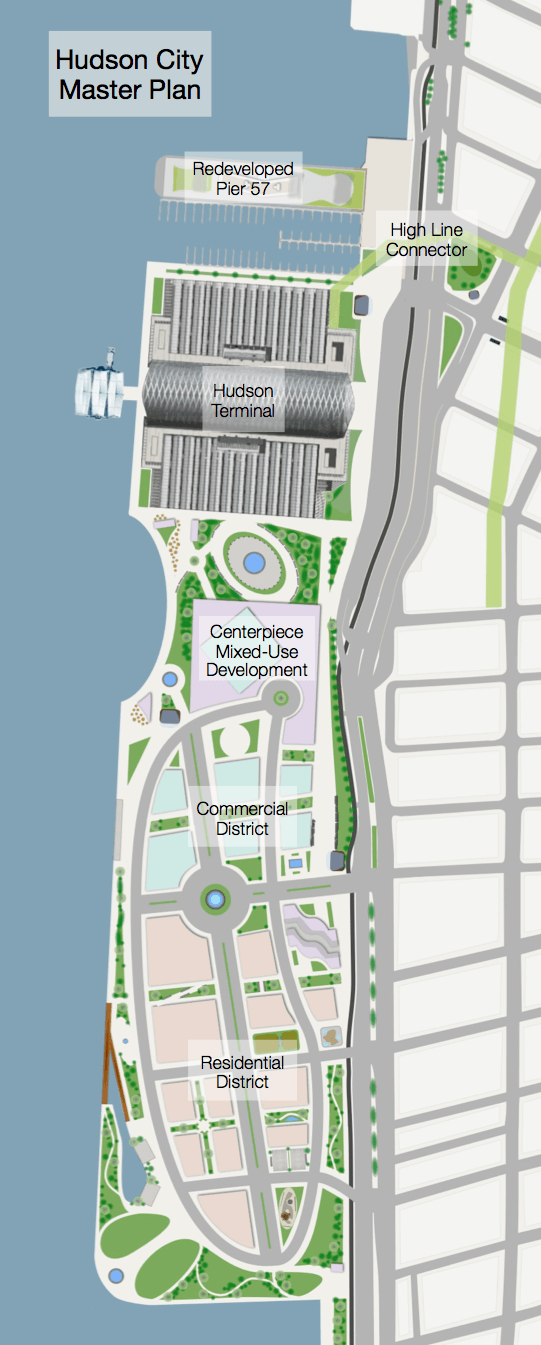

One of the greatest opportunities for TOD within a new Northeast Corridor comes from the vicinity of the proposed Hudson Terminal in New York. From New Jersey, the four-track Hoboken Tunnel would breach the New York pierhead line in the area of Pier 45 at West 10th Street, whereabout it would curve northwards along the waterfront and branch out to 26 station tracks. In total, the feeder and station tracks from the pierhead line up to the station would stretch for approximately 13 blocks along the Hudson River. In order to secure this track infrastructure, Hudson Terminal would require the installation of a slurry wall-reinforced “bathtub” similar to the one used at the World Trade Center or the utilization of landfill similar to the land underlying Battery Park City. Either way, the construction of Hudson Terminal will result in the creation of approximately 80 acres of new land, upon which significant development could occur. Acting as a southern extension of the large-scale redevelopment already occurring on Manhattan’s West Side, this new “Hudson City” would help to catalyze the implementation of Hudson Terminal Plan through economic development and multiple value capture mechanisms.

Like the HYRP, the Hudson City master plan would require zoning changes to allow for the construction of a mixed-use neighborhood over the Hudson Terminal infrastructure. However, unlike the HYRP, the land upon which Hudson City would be built would be both vacant and government-owned. Thus, bonds used to finance Hudson Terminal’s construction could be secured and repaid by fees received through the sale of lots within Hudson City as well as the sale of additional TDRs and DIBs. In order to further capture value from Hudson City developments, the agency overseeing the implementation of the Hudson Terminal Plan could also impose special assessment taxes on new developments within the site.

In total, Hudson City would encompass 8 million square- feet of new commercial space, 1.2 million square feet of new retail space, 10,000 new residential units, and 25 acres of new park and public plaza space. By constructing a major transit hub on the waterfront, Hudson Terminal will be able to capture a far greater percentage of the added value from TOD than would be possible from improving transportation infrastructure within an already built-out site in Manhattan.