The Realities of Relocating Madison Square Garden

For the better part of the last two decades, New York City’s urban planners and transit advocates have been attempting to solve the problems associated with growing ridership and congestion within Penn Station. While government leaders have yet to put forth a unified plan that comprehensively tackles the complex challenges facing the metropolitan region’s transportation infrastructure, one of the the most public proposals to address at least some of these challenges has been the call to demolish and relocate Madison Square Garden and rebuild Penn Station in its place. The coordinated public advocacy campaign in support of this plan, called Penn 2023 and led by the Alliance for a New Penn Station, was so successful so quickly that in 2013, the New York City Council denied Madison Square Garden’s request for a perpetual operations permit and instead granted them a permit to operate until just 2023 (hence the name Penn 2023).

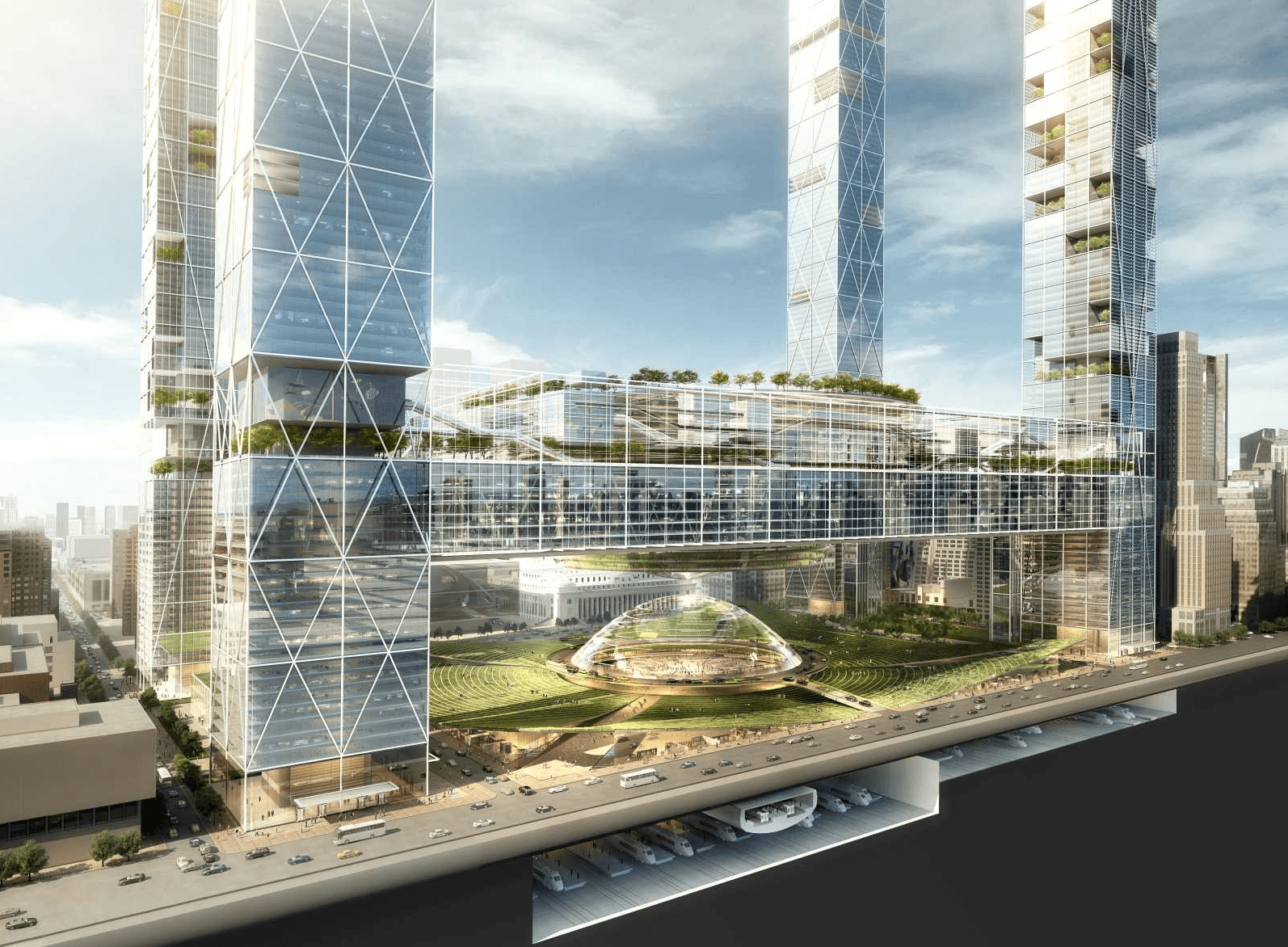

Since the push to displace Madison Square Garden began, efforts have centered on recruiting architectural firms to design futuristic visions of a new Penn Station complex. Less exciting issues—ranging from legal and financial hurdles to sustainability and neighborhood preservation—have been mostly glossed over in favor of dramatic renderings of these firms’ conceptual designs. During this time, alternative proposals have not been widely discussed, let alone seriously entertained. However, this all changed at the Municipal Art Society’s 2014 Summit for New York City, where the Alliance for a New Penn Station discussed their latest report entitled Madison Square Garden: Shaping the Future of West Midtown, which made significant progress towards addressing the realities of the Madison Square Garden/Penn Station situation.

The Good

The greatest evidence of this progress in the Alliance for a New Penn Station’s latest report comes from their admission that relocating Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station may be unachievable in the foreseeable future. As put bluntly, yet realistically, by their report, “there needs to be a Plan B.” And the bitter truth is that, despite the urgency for a renewal of the City’s regional rail systems, there may simply be too many hurdles to practically relocate Madison Square Garden and rebuild Penn Station by 2033, let alone 2023. In response, the Alliance for a New Penn Station suggested a number of sensible improvements to the current Madison Square Garden/Penn Station site that would greatly enhance the station’s usability.

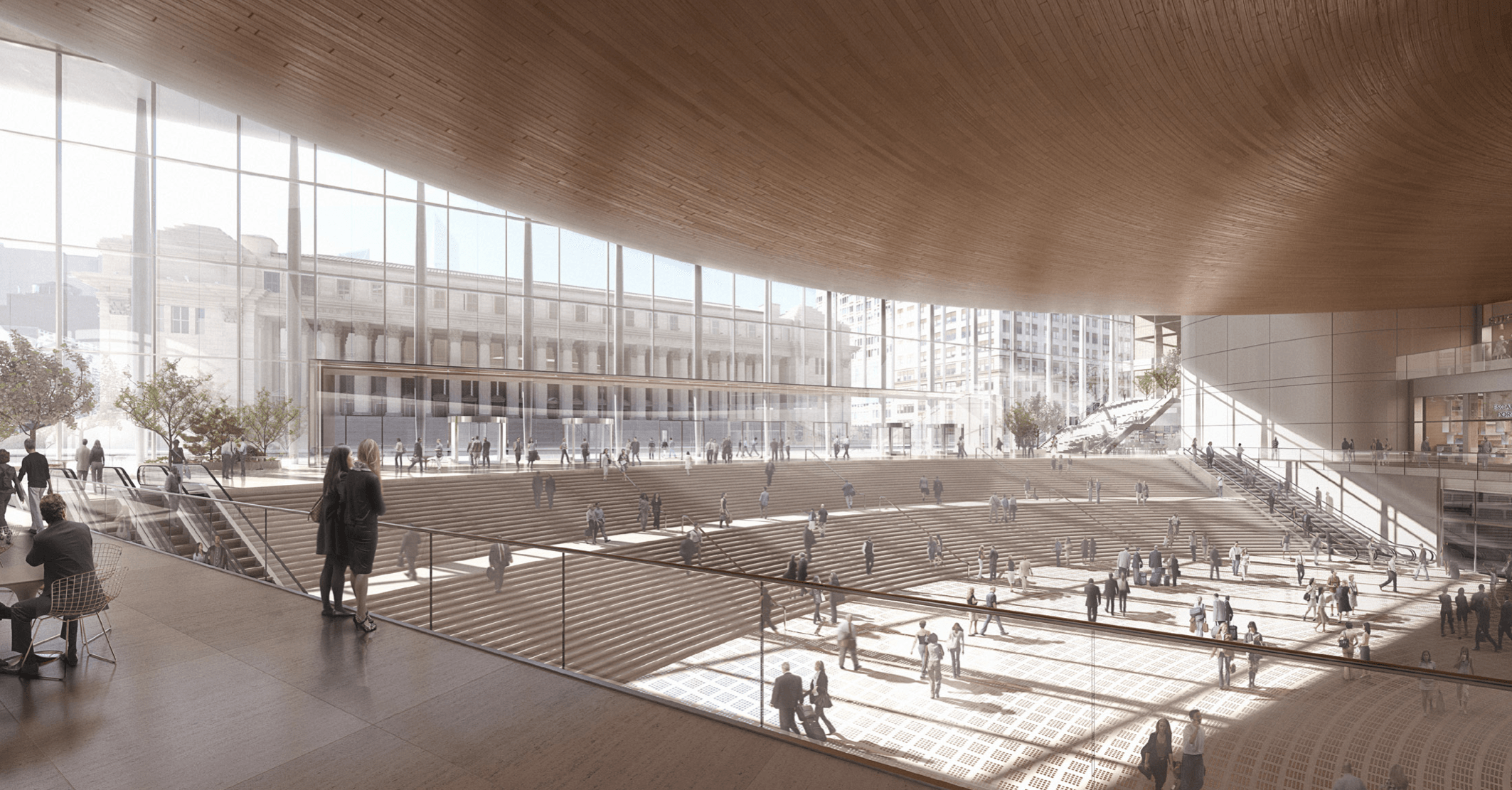

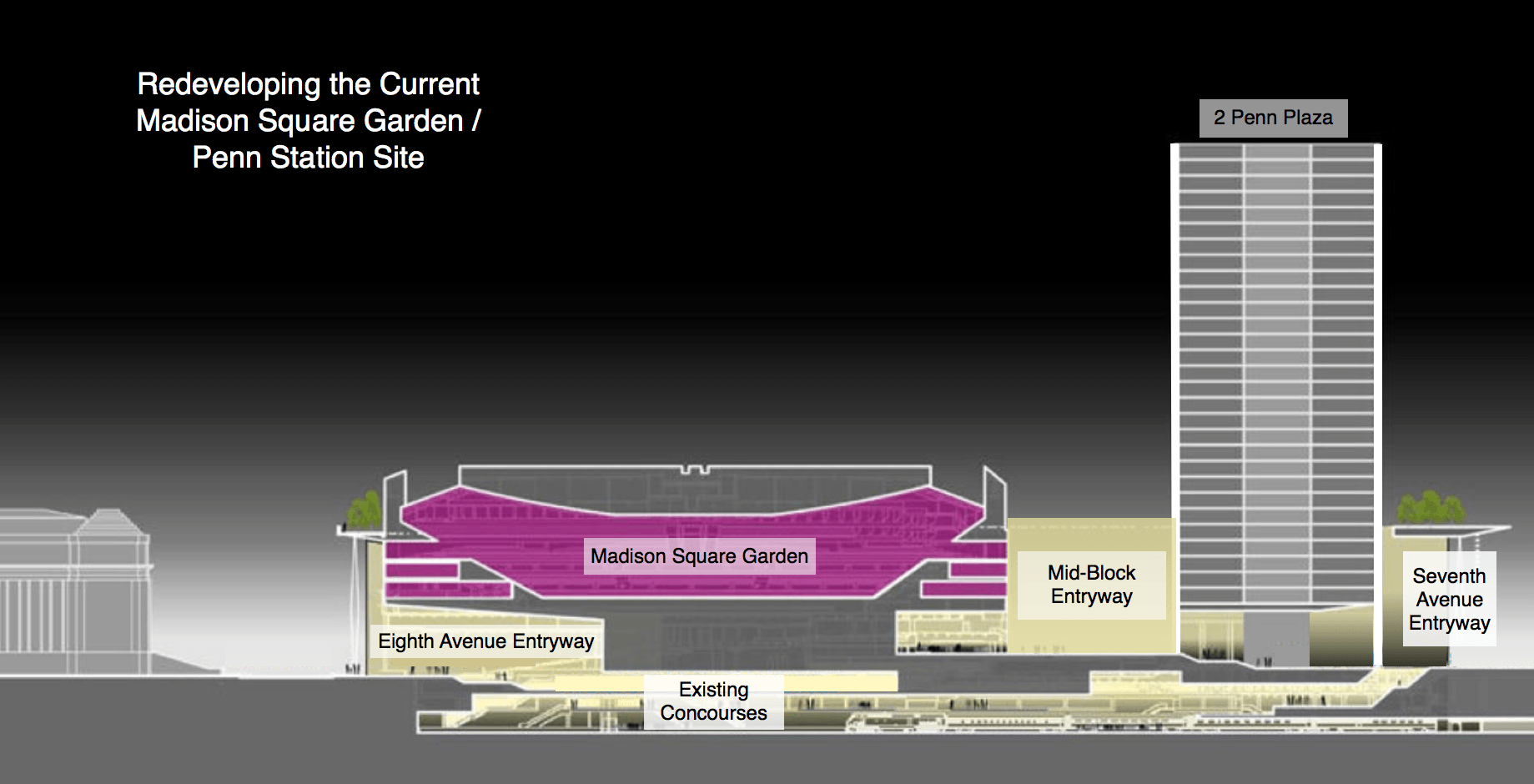

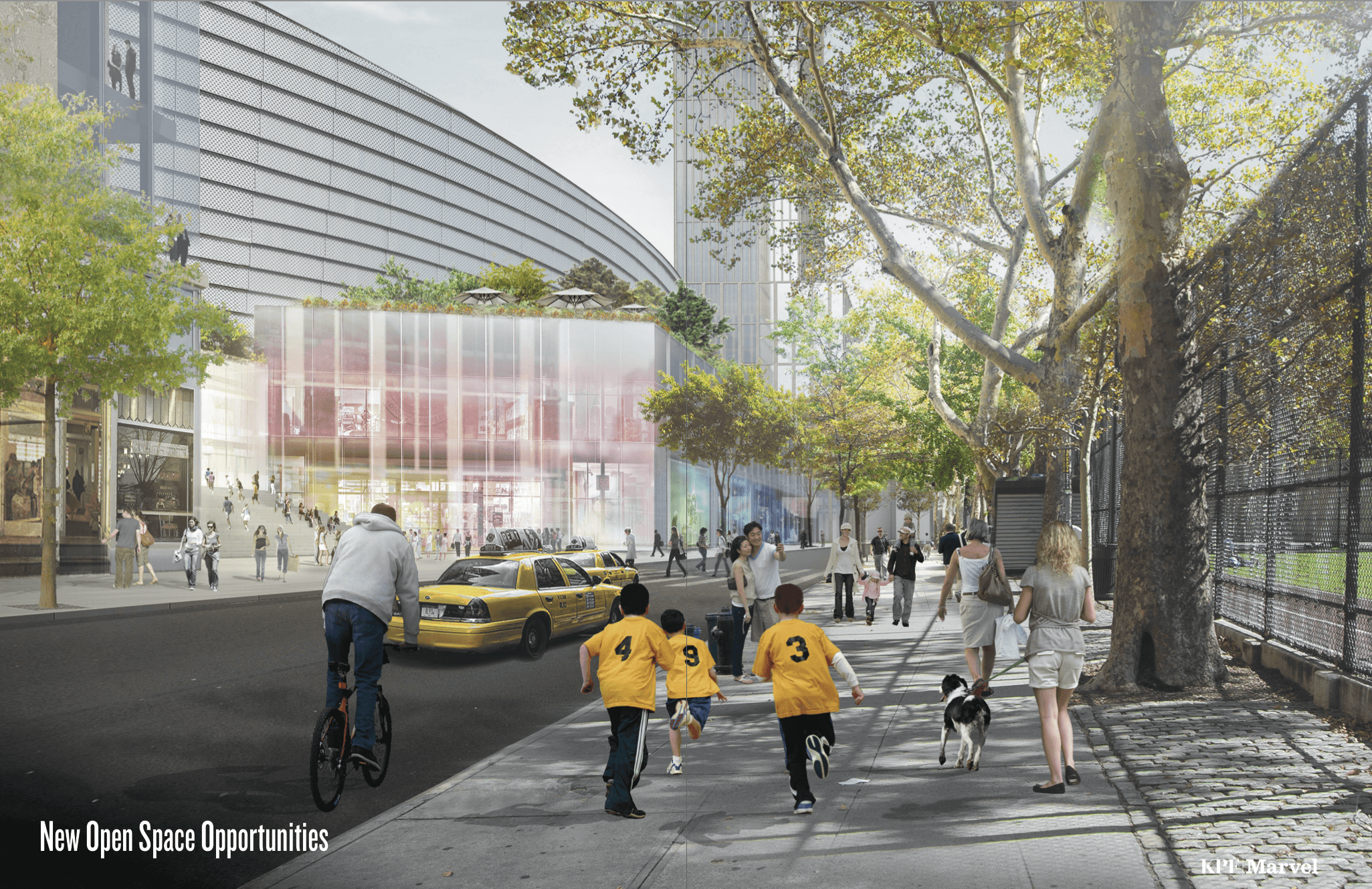

Among these suggested improvements, the Alliance for a New Penn Station (in a segment presented by Jeffrey Holmes of Woods Bagot) proposed converting the current Theater at Madison Square Garden into a new two-block-long, columnless train hall and entryway facing Eighth Avenue. This new space—which is only technically possible because the Madison Square Garden arena floor sits approximately five floors above street level—would eclipse the size of Grand Central Terminal’s main concourse. Not only would this create a vibrant and open area for passengers, but it would also facilitate the greater incorporation of the Moynihan Station development across Eighth Avenue. Unlike Madison Square Garden, which seats over 20,000, the Theater at Madison Square Garden seats only 5,500 and would be significantly easier and less costly to relocate. The Alliance for a New Penn Station also proposed constructing new retail and park space above and around this new train hall to further foster growth within the surrounding blocks and “weave those streets more forcefully into the fabric of the surrounding neighborhoods.” While this is not the first time that either transit advocates or real estate developers have suggested repurposing the space within the Theater at Madison Square Garden, the inclusion of this alternative in the Alliance for a New Penn Station’s latest report represents a major shift in direction for the Penn 2023 initiative and opens up the possibility of including yet other alternative proposals in their overall planing efforts.

The Alliance for a New Penn Station conceded, however, that improving Penn Station in its place “would likely be unable to address the severe limitations of the tracks and platforms.” While it is true that the renovation of Penn Station may not address these limitations in full, it is unclear how the relocation of Madison Square Garden and rebuilding of Penn Station in its place would fare by comparison. Removing columns from platforms and opening up passenger spaces throughout the entire Penn Station site would indeed facilitate a faster boarding and alighting process. But truly easing train congestion through Manhattan will, to a much larger extent, hinge upon the improvement of the metropolitan region’s broader rail infrastructure systems. Nevertheless, there are still other opportunities to open up platforms and improve train access within the current Penn Station site that do not require the relocation of Madison Square Garden. One example is the conversion of the current mid-block taxiway into an above ground entryway stretching the length of the station. Further, because there is no building structure above this space, track and platform columns may be removed below grade and the entire space could be lit naturally. In addition, a single-track tunnel from New Jersey to Penn Station would greatly reduce inbound and outbound congestion and allow for deferred maintenance to the existing pair of 100-year-old North River Tunnels. Finally, these improvements could be accomplished at a fraction of the cost of Amtrak’s massive $15 billion Gateway Program or the estimated $10 billion it may cost to relocate Madison Square Garden and rebuild Penn Station. And planning within the bounds of the current site would still allow for the creation of a “brand new identity for Penn Station while preserving and amplifying Madison Square Garden’s identity.”

The Bad

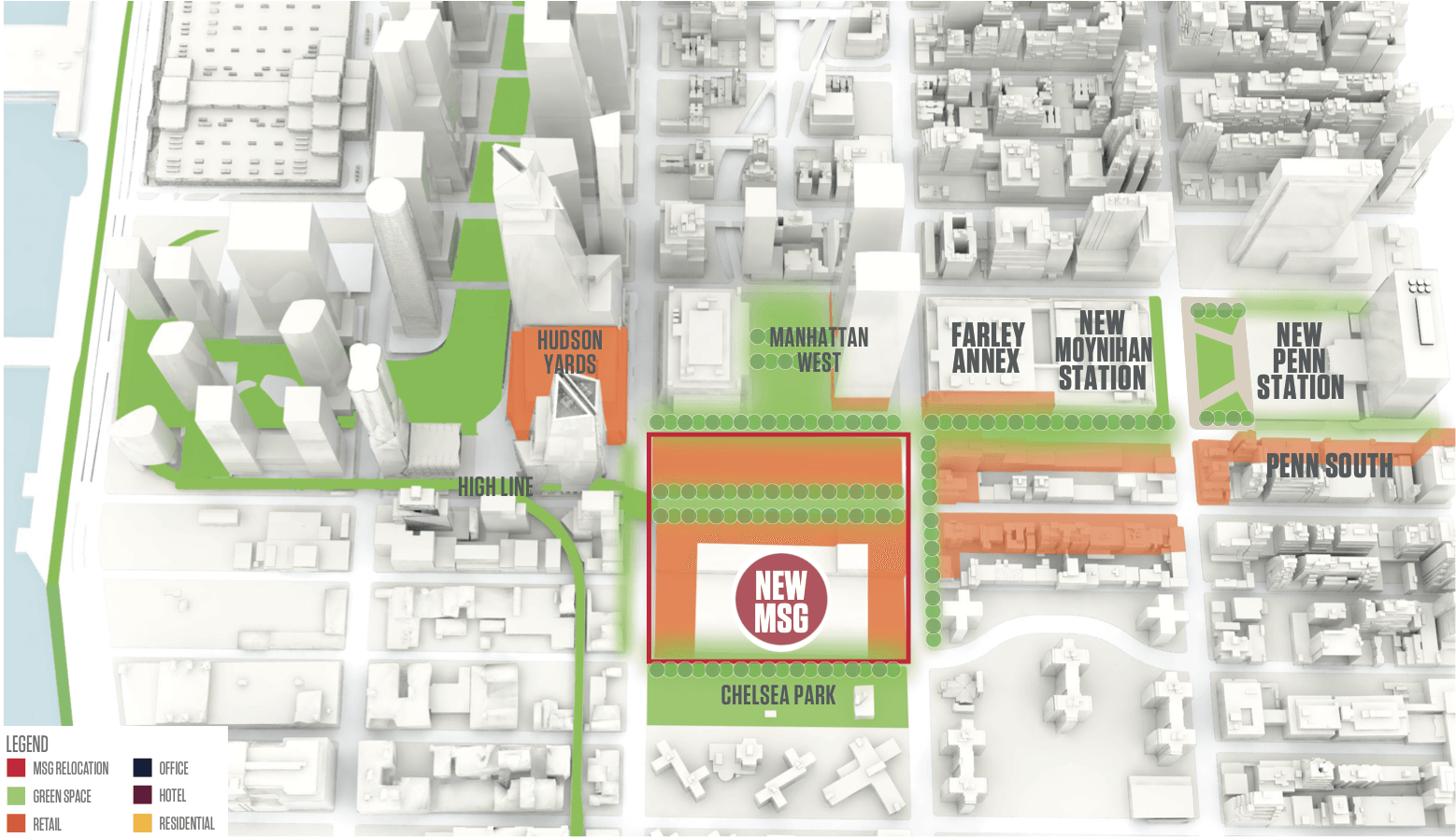

Despite their recent acknowledgement that the relocation of Madison Square Garden may not be achievable, the Alliance for a New Penn Station still focused the bulk of their report on working towards achieving this goal. At the center of this effort is the proposal that a new Madison Square Garden be built at the current site of the USPS’s Morgan Post Office on a newly created superblock between 28th and 31st Streets and Ninth and Tenth Avenues. Unfortunately, the report fails to sufficiently discuss the potential negative consequences of relocating a 20,000-seat arena to this proposed site within the center of Chelsea.

First, while the importance of adequate transportation connections cannot be downplayed in the planning for any new large-scale sports and entertainment complex, the Alliance for a New Penn Station appears to do just that in the planning for a new Madison Square Garden. During the planning stages of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn, the president of the Municipal Art Society at the time, Kent Barwick, stressed the potential problems with locating a large arena in an area without sufficient transit access:

[W]e are deeply concerned that, if built without the proper transportation policy, an arena could easily blight the surrounding area and bring nearby streets to a standstill. Our support of the concept of building an arena on the site is therefore entirely conditional on the necessary transportation mitigations being in place....

Kent Barwick, former President of the Municipal Art Society, in a September 29, 2006 letter to the Chairman of the Empire State Development Corporation

Yet, today, the proposed site for a rebuilt Madison Square Garden would be in one of the more isolated locations for walkable mass transit within midtown Manhattan. The Alliance for a New Penn Station noted that “[a] new arena on the Morgan site would be a short 4-7 minute walk to Penn Station, nearly the same distance as Brooklyn’s Barclays Center is to its neighboring transit hub, which is a 1-5 minute walk depending on point of departure.” However, the report did not lay out the walking distances to the closest subway entrances, which account for the dominant mode of public transit in the area. From the majority of exit points at a relocated Madison Square Garden, any nearby subway option—including the 7-Line at 34th Street and 11th Avenue, A/C/E-Lines at 34th Street and Eighth Avenue, or the 1-Line at 28th Street and Seventh Avenue—would be about a half-mile away and would take closer to 10 minutes to reach than the “4-7 minute walk” described by the report. The Barclays Center, on the other hand, has direct access to nine subway lines and LIRR just steps from the main entrance of the arena. Further, while one version of the plan called for the construction of a “new long-distance bus facility” adjacent to the relocated arena, there would be no direct connections to any mass transit from this facility, which would usher in dozens of daily busses to a terminus directly across the street from the neighborhood’s only full-block city park.

To that end, the report also failed to sufficiently address the impact of a relocated Madison Square Garden on the adjacent residential neighborhoods and local businesses. Unlike the current Madison Square Garden site, which sits in the middle of a dense commercial district, the proposed rebuild site is currently situated within a relatively low-density residential neighborhood, which includes the Penn South affordable housing cooperative development and aforementioned Chelsea Park. For the residents and small business owners in the area, the influx of tens of thousands of concertgoers and sports fans as well as mandatory back-of-the-house operations would likely overwhelm the current character and functionality of the existing neighborhood. Because of the lack of direct mass transit connections, automobile traffic would congest the surface roads adjacent to the arena, which already include the southernmost entryway to the Lincoln Tunnel at 30th Street and Dyer Avenue. The construction of a new Penn Station, which would incorporate Amtrak’s Gateway Program, would also require the taking by eminent domain and demolition of scores of privately-owned buildings and residences across three midtown blocks in between 30th and 31st Streets and Ninth and Sixth Avenues. While the Regional Plan Association has supported the use of eminent domain on “select properties” in the past, the scope of property seizures necessary to implement the reconstruction of Penn Station would be at levels not seen in New York City since the 1960s.

Finally, despite recognizing the “need for leadership” as planning moves forward, the Alliance for a New Penn Station has neither suggested the means of financing the construction and maintenance of a new Penn Station nor have they accounted for an estimated total cost or timeline for completion. One of the chief reasons why Real Transit put forth the Hudson Terminal Plan was to offer alternative ways of making comparable public transit improvements without the high costs of working within the Penn Station site. These methods include utilizing existing infrastructure and service to dramatically expand capacity and capturing value from transit-oriented developments to help secure financing. Even though it has become increasingly difficult to commence large-scale transportation projects in the metropolitan region, the Alliance for a New Penn Station has seemingly suggested working towards the most complex and costly solution available.

The Bottom Line

The Alliance for a New Penn Station and its member organizations have successfully focused the public’s attention on the need to renew the metropolitan region’s transportation infrastructure. And as aptly stated in their latest report, “[a]ddressing all of these challenges will require creative, new approaches.” But before decisions are made as to the best path forward, there must be a serious discussion of the differences in impact and cost between their Plan A (relocating Madison Square Garden and rebuilding Penn Station), Plan B (renovating the existing Madison Square Garden and Penn Station site), or an alternative plan not yet formally presented.

However, regardless of the chosen path, proposals should strive to prioritize the most pressing needs of the metropolitan region over more superficial aims. For instance, New York needs expanded cross-Hudson rail capacity and more efficient transit management more than it needs upgraded concourse spaces. New York also needs a greater diversity of choice for its regional rail routes and new, sustainable methods of financing transportation infrastructure projects more than it needs cosmetic improvements to its stations. The Alliance for a New Penn Station noted that “[u]nearthing the Garden and all of its support columns and utilities would allow for a complete overhaul of Penn Station, providing an opportunity to build a new city landmark.” But there are other opportunities to build new city landmarks that provide substantial public benefits at significantly lower costs and without the need to demolish and relocate Madison Square Garden. Thus, moving forward, it is imperative that government leaders seriously consider all the options available for progress, especially the ones requiring “creative, new approaches.”