Table of Contents

Download Planning for a New Northeast Corridor:

Download The Hudson Terminal Plan:

Download the Trends & Opportunities Report:

Where There Are Identifiable Problems, There Are Workable Solutions

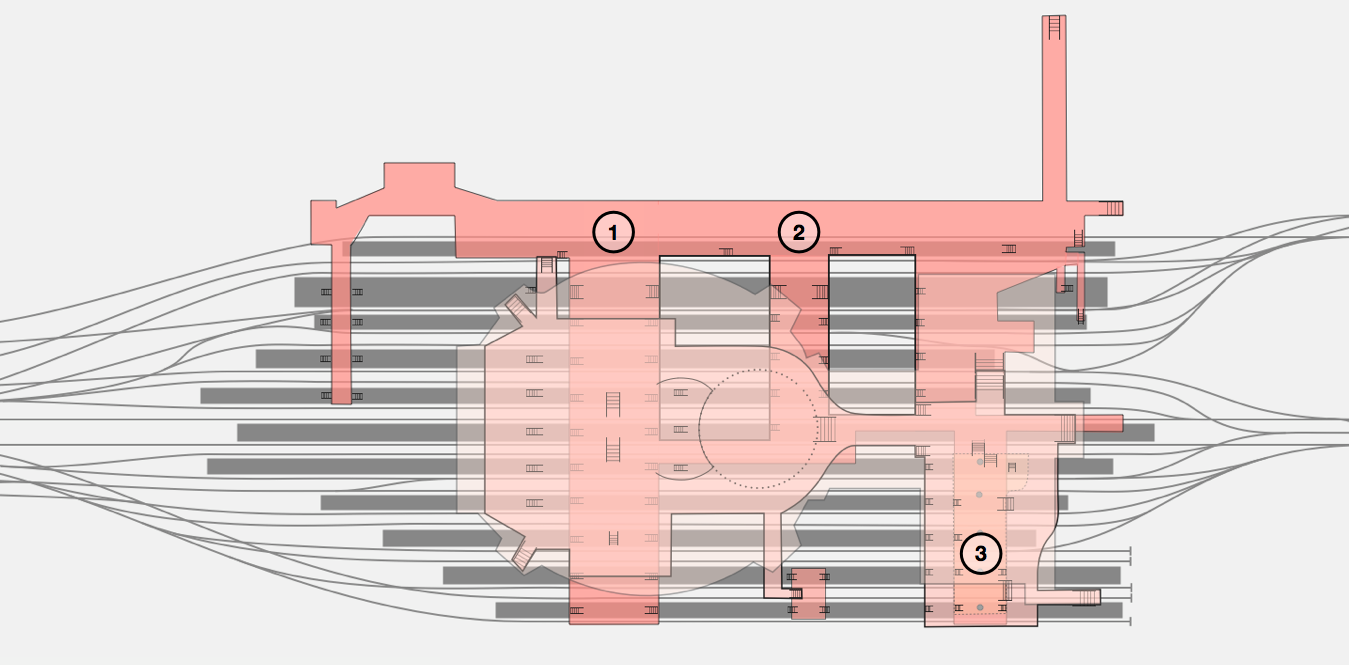

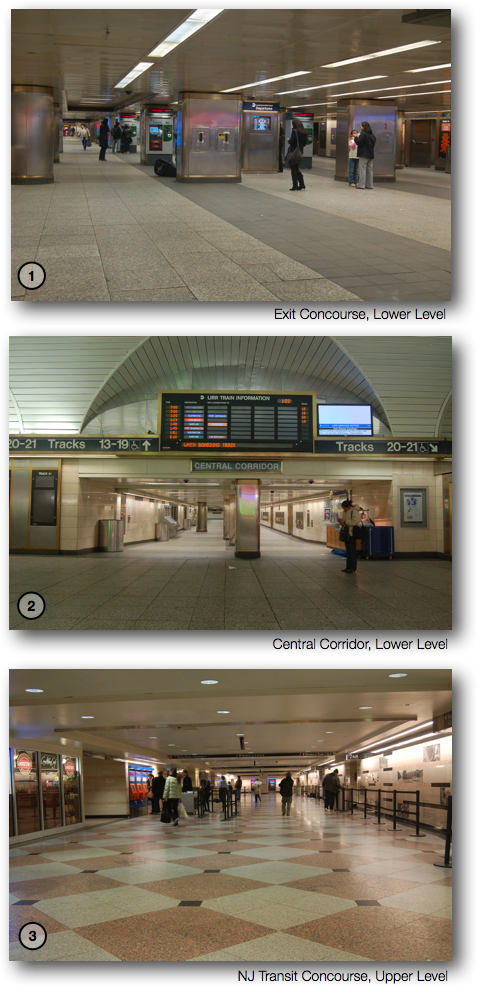

Penn Station Floor Plan

For starters, Penn Station needs a

Penn Station also desperately needs

From an oversight perspective, Penn Station also needs to

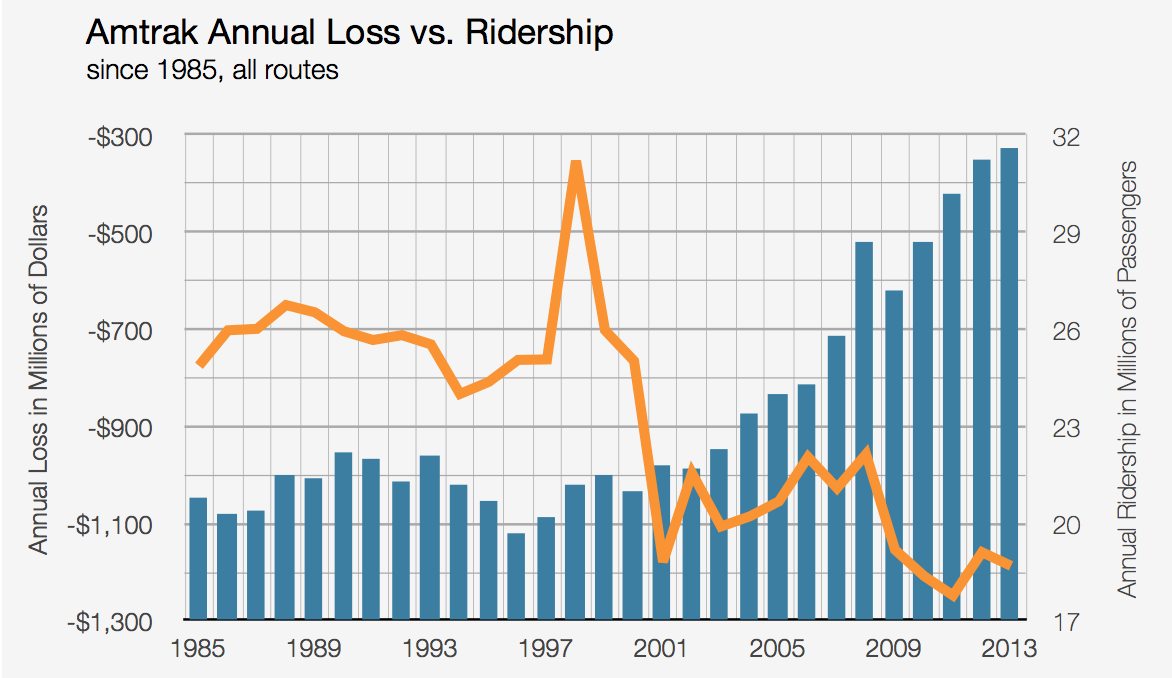

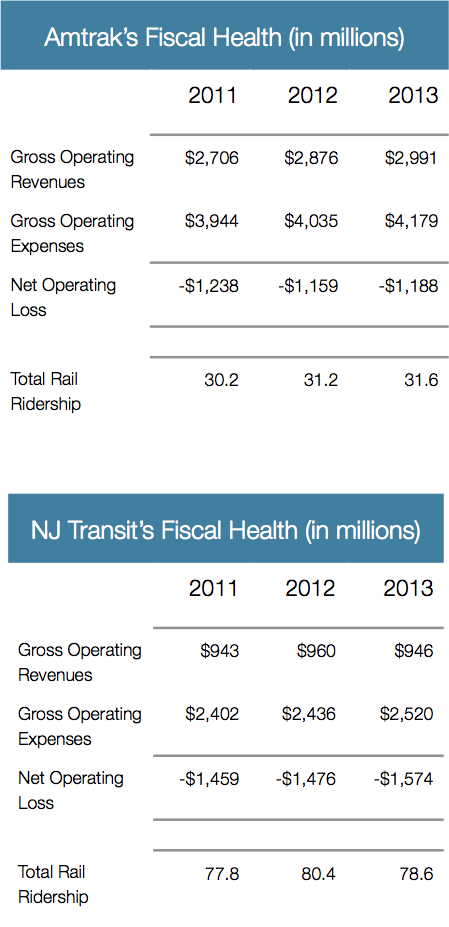

In terms of budgeting, Amtrak has, over the past three years, received federal subsidies averaging $1.5 billion and has seen ridership steadily climb from around 21 million passengers in 2000 to over 31 million passengers in 2013. However, despite this apparent growth, Amtrak has operated at an average loss of over $1.2 billion since 2009. As the chart above indicates, curiously, as Amtrak’s ridership increases, its yearly operating losses continue to grow in the negative. How is it that Penn Station’s owner could be so far in the red? The explanation is that despite its apparent success within Penn Station and even the Northeast Corridor, the remainder of Amtrak’s operations are highly unprofitable. As a result, Amtrak looks to Penn Station as a tentpole to prop up its losses elsewhere in the country.

As Amtrak continues to lose over a billion dollars each year, NJ Transit and LIRR would be justifiably concerned that its financially unstable landlord may be pressured to squeeze additional capital out of Penn Station in order to refinance its less successful sectors. This fear was indeed realized in 2001, when Amtrak was forced to put up Penn Station as collateral for $300 million in loan guarantees. As party politics increasingly threaten federal transportation funding, there are no assurances that Amtrak will continue to receive the vast federal subsidies upon which it relies. Amtrak may be required to raise rents, sell off transit space, or at best, just neglect to make much-needed improvements throughout the station. In order to avoid these potential problems, the operator of New York’s premiere transit hub needs to have both unified interests with the passengers it serves as well as sound financial footing.

It must also be noted that Amtrak is in direct competition with NJ Transit for passengers along the Northeast Corridor (which is also owned by Amtrak and leased by NJ Transit). For instance, a person wishing to travel from Penn Station to Trenton, NJ at noon on a weekday has the option of either taking a 90 minute NJ Transit train for $16 or a 50 minute Amtrak train for $40. While the relationship between Amtrak and NJ Transit is currently civil and complementary, Amtrak holds all of the cards. Further, Amtrak’s monopolistic control of Penn Station is at odds with its little relative use of the rail hub; on a given weekday during peak hours, Amtrak comprises only 3% of the station’s ridership. It is simply bad public policy for NJ Transit and LIRR commuters to rely upon an at-capacity station run by an unprofitable landlord who also happens to be a competitor. Competition is a good thing, but Amtrak currently has a monopoly over NJ Transit’s service to Manhattan.

Perhaps most importantly, Penn Station needs to

The second, and more effective, way to improve Penn Station’s capacity constraints is to reduce the demand for travel into Penn Station. This idea is already being implemented for LIRR by the MTA through the East Side Access project, which seeks to reroute a number of LIRR trains into a new eight-track station below Grand Central Terminal. This will provide commuters from Long Island the option of traveling to either Penn Station or Grand Central Terminal depending upon their ultimate destination. However, both Amtrak and NJ Transit still utilize only one Manhattan terminus and one pair of tunnels to enter New York City from New Jersey. In order to responsibly and permanently address the growing demand for rail travel in the metropolitan region,