Table of Contents

Download Planning for a New Northeast Corridor:

Download The Hudson Terminal Plan:

Download the Trends & Opportunities Report:

Capturing Value Through Transit-Oriented Development

Transit-Oriented Development (“TOD”) involves the strategic and mutually-beneficial construction or redevelopment of mixed-use properties in the immediate vicinity of a transportation infrastructure project. Successful TODs add value to a given public transportation project by not only encouraging new ridership, but also catalyzing economic development. To that end, where transit projects have difficulty securing funding through traditional routes, a comprehensive TOD plan may assist in raising capital by leveraging future development revenues in exchange for financing. Government agencies traditionally help to implement successful TODs through the imposition of district-specific zoning changes, issuance of bonds, and utilization of a number of strategic value capture mechanisms.

The Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project

In New York, one of the most prominent examples of the mutually beneficial relationship between transportation improvements and TOD is the Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project (“HYRP”). In the early 2000s, and in conjunction with a bid to host the 2012 Olympics, the City of New York and MTA proposed extending the 7-Line Subway to Manhattan’s West Side at 34th Street and 11th Avenue and redeveloping the adjacent, underdeveloped areas. However, despite the City’s advocacy for the project, the MTA (a state agency) had already prioritized funding for other transit projects including the LIRR’s East Side Access and Second Avenue Subway. Viewing the 7-Line Subway Extension as an opportunity to catalyze economic development along Manhattan’s West Side, the Bloomberg Administration sought to fund the transportation project independently of the MTA by leveraging future TOD revenues in exchange for financing. The first step towards achieving this goal involved the rezoning of 45-blocks of mostly manufacturing space in the vicinity of the 7-Line Subway Extension to allow for the future commercial and residential development. This zoning amendment allowed for the creation of 25.8 million square-feet of office space, 20,000 housing units, two million square-feet of hotel space, one million square-feet of retail space, and 20 acres of parks and open space, including the ten-block Hudson Park and Boulevard in between 10th and 11th Avenues.

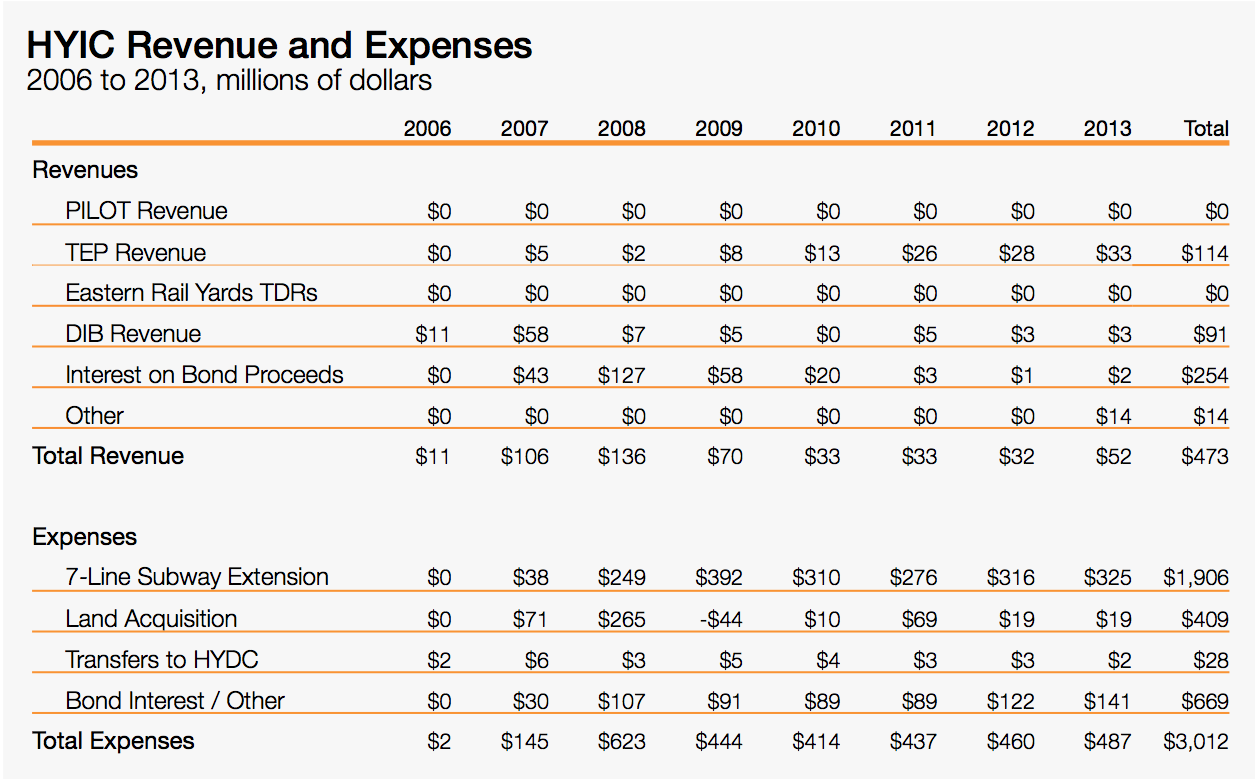

In order to facilitate the HYRP, the City of New York created the Hudson Yards Development Corporation (“HYDC”) to manage the planning, design, and development of the project area, not including the actual 7-Line Subway Extension, which would be managed by the MTA. The City also created the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (“HYIC”) to finance the capital improvements required to implement the HYRP. Since 2007, the HYIC has raised $3 billion in proceeds from two bond offerings. In order to secure and repay these bonds, the HYIC and HYDC put forth several means of capturing the added value of the new real estate developments under the HYRP. The largest source of revenue is set to come from commercial payments in lieu of taxes (“PILOTs”). Under a PILOT arrangement, the New York City Industrial Development Agency (“NYIDA”) would purchase the land to be developed from a developer for a nominal amount, which would in turn relieve the developer from paying traditional property taxes. Thereafter, over the course of the next 30 years, the developer would pay a determined price per square foot to the NYIDA, who would then transfer those proceeds to the HYIC. At the end of the 30 years, the property would be sold back to the developer for a nominal price and the developer would resume paying normal property taxes. In order to incentivize new developments prior to the build-out of the site, the NYIDA was empowered by the City to discount the PILOT rates below normal property tax rates depending on location and completion date of a given development. For those developers that opt out of the PILOT program, the City of New York has agreed to repay the HYIC all property taxes received from properties constructed after 2005 in the form of Tax Equivalency Payments (“TEPs”).

Another source of revenue for the HYIC will come from the sale of various transferrable development rights (“TDRs”) tied to the development of the eastern half of the MTA’s West Side Yard (the “Eastern Rail Yard”). Developers are traditionally allowed to build, as-of-right, a building with a maximum total floor area comprised of the sum of the lot size multiplied by the zoned floor-area ratio (“FAR”) for the given lot. For instance, a developer looking to build an office tower on a 10,000 square-foot lot with a FAR of 6 can construct, as-of-right, a 60,000 square foot building. The City’s zoning changes increased the as-of-right and maximum FARs for the Eastern Rail Yard to allow for the construction of 10.8 million square-feet of new mixed-use space. However, since the HYRP requires the incorporation of parks, large public plazas, and other non-commercial elements throughout the project site that restrict maximum development, the MTA was only able to lease 5.1 million square-feet of development rights over the Eastern Rail Yard, which is set to raise over $1 billion in rental payments over the 99-year term of the lease. In 2007, the HYIC purchased from the MTA a 50% interest in over 4.5 million square-feet of TDRs from the unusable space over the Eastern Rail Yard for $200 million. Hudson Yards developers wishing to increase a given property’s FAR may purchase these TDRs, of which the proceeds will go to the HYIC until it recoups its initial $200 million investment plus interest. The proceeds from sale of these TDRs after this point will then go to the MTA. Developers may also increase their FAR through the purchase of District Improvement Bonuses (“DIBs”) from the HYIC, which function in a similar manner to the Eastern Rail Yard’s TDRs. While they are priced somewhat differently, today, TDRs and DIBs may be purchased for approximately $125 per additional square-foot.

The HYIC has yet to capitalize on most of its value capture mechanisms, including PILOT and TDR revenue, because very few eligible projects have begun construction, and those that have begun construction will not be completed (and thus generate revenue) for several years. The HYIC has, however, raised over $200 million in TEP and DIB revenue since 2006 on developments that were completed during the earlier stages of the HYRP. Through 2013, the HYIC has spent nearly $2 billion on the 7-Line Subway Extension, which has been funded chiefly by its two bond issuances that raised $3 billion. The HYIC has also spent over $400 million in land acquisition and public amenity construction in order to implement various elements of the HYRP, including Hudson Park and Boulevard as well as other public spaces. As the construction of the subway wraps up in 2015 and the first large-scale developments open in the upcoming years, the HYIC will begin generating increasing revenues, which will allow them to repurchase their bonds and fully implement the HYRP. Because of the strategic partnership between transportation infrastructure improvements and real estate development, the HYRP has not only helped to facilitate the construction of an expensive transit project, but will also increase ridership, create a new livable and workable district in a previously depressed area of Manhattan, and catalyze economic development.