Table of Contents

Download Planning for a New Northeast Corridor:

Download The Hudson Terminal Plan:

Download the Trends & Opportunities Report:

New York’s Transportation Landscape

Local Rail Conditions

New York City enjoys one of the most diverse and dynamic transit systems on the planet. From a regional perspective, four rail systems—Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), New Jersey Transit (NJ Transit), Metro North Railroad (Metro North), and Amtrak—usher commuters and travelers into two hub stations: Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal.

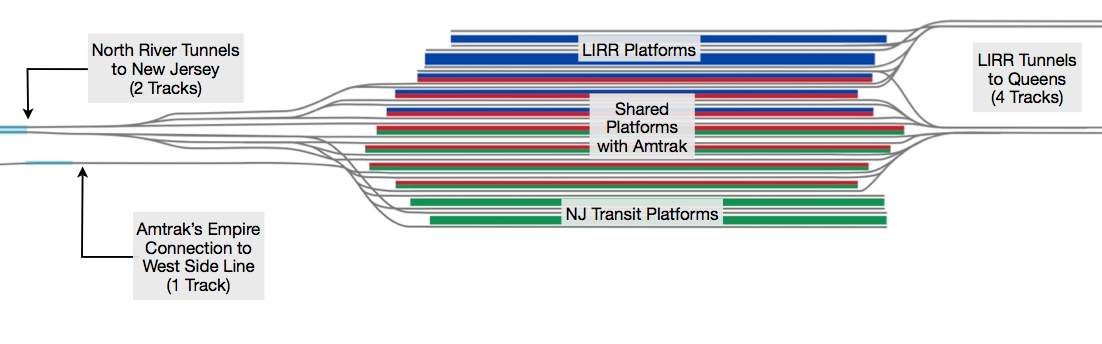

Penn Station is the main transit hub servicing Manhattan’s West Side and Grand Central Terminal is the main transit hub servicing Manhattan’s East Side. However, compared to Grand Central Terminal, Penn Station possesses significantly less train capacity. Grand Central Terminal provides Metro North with 44 tracks over two levels, with four feeder tracks entering the terminal from points north. On the other hand, Penn Station provides NJ Transit, Amtrak, and LIRR just 21 tracks over one level. Compared to Grand Central Terminal’s ratio of 44 tracks per one rail system, Penn Station has an average ratio of just 7 tracks dedicated to each of its three rail systems. Further, while LIRR uses four feeder tracks coming from Queens, NJ Transit uses just two feeder tracks traveling into Penn Station, which it shares with Amtrak along the Northeast Corridor. Overall, the capacity at a given moment for commuter rail systems in Penn Station is abysmal. Yet Penn Station handles twice the demand for rail traffic as Grand Central Terminal, and more rail traffic than any other station in North America. The need to alleviate Penn Station’s capacity constraints could not be more apparent. But Penn Station’s broader challenges stretch far beyond its capacity issues.

An Overview of Penn Station

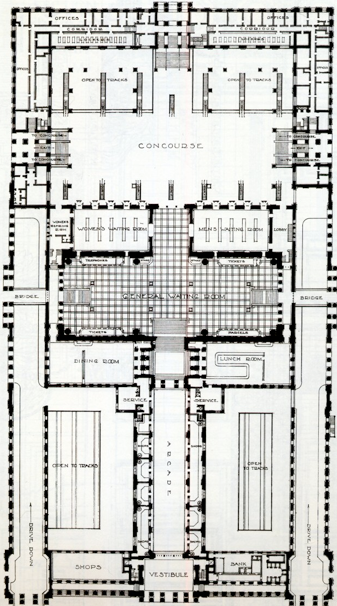

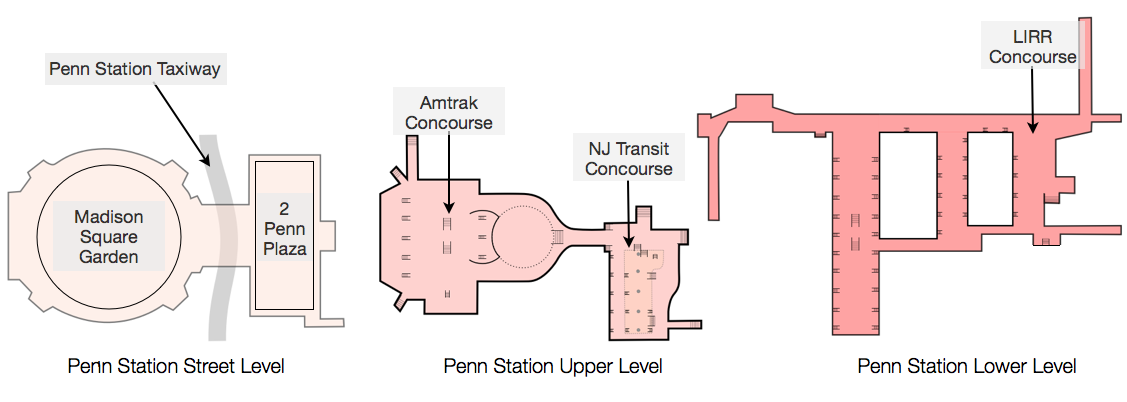

It goes without saying that Penn Station is ugly, cramped, dirty, and, some may say, depressing. But critics of reform often argue that train stations are not built to be beautiful. They are meant for traveling and commuting in the fastest and most efficient way possible. However, it is in this context that Penn Station is truly a failure. Simply put, because of its disjointed design, Penn Station is unable to efficiently move people between transit systems and their ultimate destinations. The ugliness happens to be the added consequence of a fundamentally flawed design. Of course, the original Penn Station (1910-1963) did not suffer from the same design deficiencies as its successor. The original Penn Station enjoyed an extra large, central waiting room with soaring ceilings and convenient connections to other sections of the station. The singular main concourse provided access to all of Penn Station’s platforms from a unified location, with a vast, open floor to move freely between points.

Penn Station Track Diagram

In the 1960s, as demand for rail travel fell, Penn Station went into disrepair and critics argued that its eight acre footprint would be better used for other purposes. Accordingly, from 1963 to 1968, the original structure was razed and Madison Square Garden and Penn Plaza were built above it, relegating Penn Station to the basement levels of the complex. Over time, Penn Station, which used to exclusively serve the Pennsylvania Railroad, was sectioned off for three different rail operators: Amtrak, NJ Transit, and LIRR. Of course, three separate train systems occupying a space of the same size meant that each system had less space to work with. Instead of having a unified central concourse serving all trains, today, each section of the station is maintained and styled differently by its respective operator. As shown by the track diagram above, Tracks 1-4 are used exclusively by NJ Transit and Tracks 5-12 are shared by Amtrak and NJ Transit trains. LIRR has the exclusive use of Tracks 17-21 on the north side of the station and shares Tracks 13-16 with Amtrak. Except for the shared platforms, a passenger cannot reach the LIRR tracks directly from the Amtrak and NJ Transit concourses. Since Amtrak and NJ Transit share tracks, passengers from a NJ Transit train can wind up in the Amtrak concourse, and vice versa. This division of space has resulted in drastically smaller concourses, fewer seating areas, and more difficult navigability throughout the station.

In addition to its design troubles, Penn Station also suffers from dual-capacity problems: 1) for points west of New York City, there is only one inbound track and one outbound track; and 2) for three transit systems, there are only 21 tracks available at a given time. This lack of capacity greatly reduces the time in which a given train may idle, i.e., trains are only able to park at a given platform for a very short amount of time before having to clear the way for the next arriving train. To avoid potential backups, track assignments are made as they become available, forcing commuters to wait until minutes before departure time in order to board their train. Further, each train system is forced to use only certain tracks within the station. With small, disjointed concourses, during peak operating hours, Penn Station becomes a center for angry, gridlocked commuters. Passengers are forced to stand because there is not enough room for adequate seating. This breakdown of passenger movement makes boarding the overcrowded trains even more time-consuming, causing further delays in departures and subsequent arrivals in and out of the already at-capacity tunnels, and setting off a chain reaction across all three transit systems.

Despite the chaotic transit dance that occurs every rush hour in Penn Station, NJ Transit still claims an on-time performance rate of 91% along the Northeast Corridor. This apparent anomaly, however, is the result of dubious accounting—a train is counted as “on-time” even if it arrives up to six minutes later than its posted arrival time. Similarly, a New Jersey bound train that has shut its doors and ceased accepting passengers, but remains idled within Penn Station, is considered to have “departed“ the station despite not actually moving. Since the entire system suffers for every minute that a train is delayed, having trains arrive and depart consistently late while still being counted as “on-time” not only hurts rail passengers, but also misleads the public as to the full extent of the problem.