Table of Contents

Download Planning for a New Northeast Corridor:

Download The Hudson Terminal Plan:

Download the Trends & Opportunities Report:

Stipulations

The City of New York stands at a crossroads. For the past decade, Manhattan’s commercial districts have experienced an unprecedented building boom. Capital improvements that have been on the table for years are finally underway. But looking ahead, as we prioritize our infrastructure planning in light of fiscal instability that has threatened key metropolitan agencies, the region needs to make difficult decisions regarding its future. In one direction, the City can continue to invest in its infrastructure and real estate development to promote growth and prosperity for the region as a whole. In the other direction, the City can take austerity measures to conserve resources, but in the process, risk entering a period of decline that may threaten long-term growth.

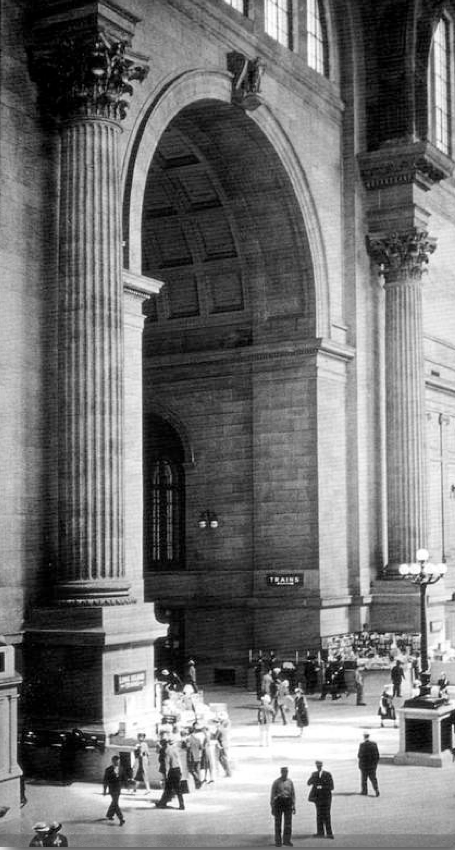

Although these circumstances may sound familiar, the year described above is 1959. And over the next two decades, instead of investing in wide-reaching mass transit projects, New York City would act conservatively, abandoning many of the pro-growth policies that created its post-war prosperity. During this time, transit workers went on strike, the Second Avenue Subway was abandoned, and the original Penn Station was demolished. As subway ridership declined, revenues fell and the transit authority cut back on station maintenance and the purchase of new equipment. In turn, fewer people rode the deteriorating subway, revenue fell, and the cycle of decline continued as New York City was unable to simultaneously maintain previously-successful transit systems while adapting to changes in the transportation and real estate demands of the region, chiefly due to the rise of the automobile and exodus of middle-class residents to the suburbs. The city had stalled because political leaders chose to invest modestly instead of planning ahead for the region’s changing needs.

There are obvious parallels to the present day. Manhattan’s commercial districts have experienced tremendous growth over the past decade and several large capital projects will be completed in the upcoming years. Yet, transit agencies such as the MTA and NJ Transit face rising budget deficits that threaten future investment. Although New York may not risk returning to the hardships faced during the 1970s and 1980s, the City does indeed stand at a crossroads. Moving forward, it is imperative that metropolitan agencies make responsible investments in transportation infrastructure and real estate development so that the region will continue to prosper in the future.

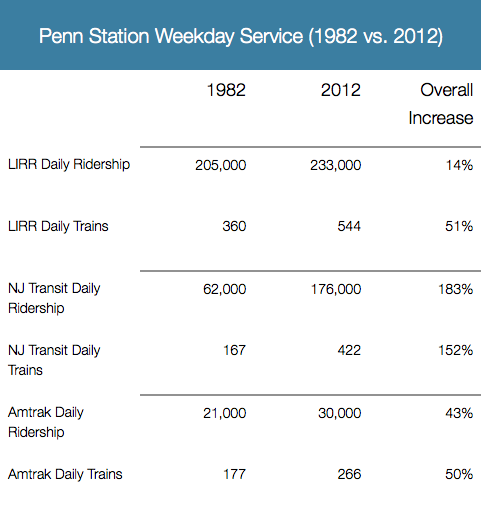

Much like the fundamental trend away from rail and towards the automobile in the 1950s and 60s, today, the trend is reversing. As gas prices rise, the middle class shrinks, and commuters increasingly choose to travel by rail, the demand for effective commuter rail and mass transit systems is quickly rising. But the region’s transportation infrastructure is outdated and cannot keep up with this increasing demand. At the heart of this problem lies the heart of the system: Penn Station. What began as a grand ode to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s success is today an unnavigable substructure beneath the Madison Square Garden complex. From a design perspective, Penn Station suffers from dual capacity problems. First, the 100-year-old pair of single-track tunnels that feeds trains into Penn Station from New Jersey severely limits the number of hourly trans-Hudson crossings. Second, Penn Station itself has a shortage of tracks and platforms, which creates unavoidable traffic within the already overburdened system already overburdened system. In spite of its shortcomings, Penn Station remains the busiest transit hub in North America. As New Jersey’s population is expected to increase by 1.7 million residents over the next 20 years, Penn Station cannot accommodate more trains during peak hours. Ridership continues to grow, but without the possibility of increases to service. For Amtrak, at a time when high-speed rail has become the focus of the future, Penn Station is not prepared to usher in a new generation of trains and passengers. It has become abundantly clear that the current iteration of Penn Station has outlived its usefulness, and a comprehensive solution is long overdue.

Over the past several years, a number of proposals have come to the forefront of the debate regarding how to address the wide-scale problems associated with Penn Station’s capacity restrictions. Many of these proposals call for the expansion or replacement of Penn Station. But during the decades it may take to reach an ultimate solution at Penn Station, there are significant opportunities to improve the status quo in the interim by looking for ways to upgrade the region’s infrastructure outside of Penn Station. And in preparing to take the next steps forward, it is crucial that any comprehensive plan seeks to accomplish a number of key goals:

1) Avoid the mistakes of the past by looking forward, not just to the immediate future, but to the long-term future;

2) Find a way to dramatically increase track and platform capacity for trains originating west of the Hudson River;

3) Develop a strategy to plan for the sustained growth of untapped areas within Manhattan’s West Side through strategic, transit-oriented development;

4) Contain costs and schedule construction aggressively so that the public does not continue to wait around as they have become so accustomed to doing; and

5) Restore pride in the metropolitan region’s great transportation infrastructure.